This is a summarized version of a long debate I had on the epistemology of conscious experience, or the debate between Direct Perception v.s. Representationalism on the PSYCHE-D mailing list in April - June, 2005. I have selected choice threads that led to interesting exchanges, with links to the original messages.

This debate is interesting not only as a discussion of the nature of consciousness, but also as a prime example of a paradigmatic debate. In fact, this issue is perhaps the ultimate paradigm debate, because the alternative paradigms present such radically different inside-out-inverted views of the world relative to each other, no wonder the opposite camps could never reach agreement even on the meaning of terminology!

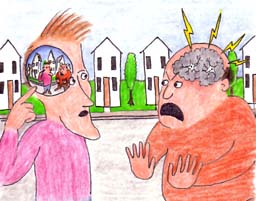

See also the Cartoon Epistemology

Initial message

Lehar: refutation of Gibsonian concept

Brook: Proof of direct perception: Kick a chair

Rickert: Gibson's epistemological error?

Lehar: Theories v.s. Paradigms

Lehar: What would it take to convince you?

Sizemore: Conceptual v.s. Empirical Issues

Sizemore: Meaning of representation

Lehar: Ontology of Experience

Lehar: Summary Direct Percepton v.s. Representationalism

Brook: What more do you want?

Rickert: No clear meaning of Representation

Rickert: Computers don't compute

Chalmers: Terminological dispute

Lehar & Brooks: offlist debate

Lehar: Analogical or analytical?

Dalton: Representation is analogical?

Reason: Is the word "red" red?

Seager: How big is your experience?

Trehub: We do not perceive our perceptions

Lehar: More paradigmatic stuff

Lehar: Still more paradigmatic stuff

Brook: Hostile to sense data theory

Lehar: Epistemology of exeperience

Lehar: Concluding exchange

Hi everyone

Regarding the most interesting discussion on projection geometry related to visual conscious experience between (primarily) Alex Green and Brian Flanagan, I highly recommend the work of Steven Lehar. See http://cns-alumni.bu.edu/~slehar/Lehar.html

He has written several books and a target article in Behavioral and Brain Sciences on this and related topics, and his work is not only insightful but (as you can see on his website) extremely well illustrated with artistic color cartoons.

Steven will be speaking at the next Tucson conference a year from now. See http://consciousness.arizona.edu/Tucson2006.htm

cheers

Stuart

From Lehar's web site:

Sizemore:

So, the ploy is simply to say that the representation is information

and information is "used" by some other part of the nervous system. By

substituting some other word for "see" (here "use" is substituted) the

glaring absurdity is obscured. But the notion of "using information"

needs to be critically examined, and when it is, it can be seen to

raise the same issues as "garden-variety" representationalism. In what

sense do nervous systems "use information"? Does it mean any more than

events cause receptors to "fire" which cause other neurons to "fire,"

and so on? If not, then we are simply saying that somehow physiology

mediates the behavioral functions that we wind up calling "seeing,"

and "hearing," etc. and this only raises issues of infinite regress

and homunculi if representationalism is assumed. If it means more

than that, then we are probably back where we started. That is, in the

conventional view, we say that we see the world, and that we do so by

creating an inner copy that is seen. But we may easily say that

animals (human and non-human)"use information" in the environment

(colors, sounds, etc.) in order to behave in the ways that we observe

and that they do this by creating an inner copy of the information

which is what is "used." If "using" information in the environment

requires further "usage" than why doesn't "using" the internal

information?

The key issue is not the word "see" or "use", to describe how the

brain makes use of internally represented information, it is the

question of whether the internal representation is processed by other

internal processes in the brain, or whether it requires a copy of the

*whole brain* in order to "see" that represented data. Only the latter

formulation leads to the infinite regress.

If Sizemore claims that a picture in your brain requires a miniature copy

of your whole brain to "see" that picture, then surely this objection would

apply to *any* information represented in the brain, including verbal,

linguistic, and cognitive knowledge, all of which would require a miniature

copy of the whole brain to interpret or process that cognitive

information. Why is it that the homunculus objection is only raised

against pictorial data? What is so special about image data that requires a

homunculus to "see", when other data do not?

Now I acknowledge a profound philosophical issue here, that applies to

*any* explanation of mental function, that is, after we are done

explaining the mechanism of perception or cognition, there is the

question of how come we get to *experience* that information

processing. The mechanistic explanation of neural signals and sensory

processing says nothing of the experience of perception and why we

have it. Even if we have actual pictures in our brain, how is it that

we *experience* those pictures? Why doesn't a computer experience the

image data that it processes? That is indeed a profound issue, but

again, it is one that applies to cognitive and verbal information

processing just as much as to pictorial processing.

But whatever the explanation might be for the

"Ultimate question" of consciousness, the indisputable fact remains

that we *DO* in fact experience the operation of our brain during

mental processing.

Steve

Lehar >

GS:

Lehar >

Glen Sizemore >

Lehar >>

Sizemore >

I acknowledge that placing a representation in the head does not solve the

whole problem of how we see. It *is* however a *prerequisite* for being

able to see something that that something must be represented in your

brain. Is it not?

Sizemore >

Yow! That's pretty radical man! I'm not sure I can debate you if we don't

even share this much in common!

Sizemore >

Wow! Thats pretty bizarre!

Do you agree with the robot metaphor, that people are like a robot

that receives sensory input, stores it in internal representations,

and processes that information in order to compute an appropriate

behavioral response? Do we at least agree on that metaphorical image?

If not, then I don't think we can have a meaningful exchange beyond just

agreeing to disagree.

Steve

Ok, NOW I understand where you guys are coming from! Its the Gibsonian /

O'Regan, "organism interacting with the environment" idea.

Well, in the first place, Representationalism has never been shown to be

false. Au contraire, mon ami, the *principle* of representationalism has

been actually demonstrated in robots that use video cameras for sensory

input, computations in a computer brain, and behavior by way of servo

actuators. Now admittedly current robots are pretty primitive

and "robotic", and very different from animal perception. But if anyone has

any ambiguity about the meaning of terms

like "information", "representation", and "processing", just look at a

robot and the concepts become perfecty clear.

Robots offer an *existence proof* that the *concept* of representationalism

is *feasable* at least in principle.

So lets have no more talk about not knowing the meaning of information or

representation or processing. Those terms are perfectly clear, and

obviously workable in principle.

Furthermore, in the absence of *compelling* evidence to the contrary, a

representationalist assumption is the most *reasonable* understanding of

perception, given the eye that appears to work like a video camera, the

optic nerve that sends data to the brain, given the complex wiring

suggestive of computation in the brain, and motor neurons from the brain

back out to the muscles as if to produce behavior. The representationalist

thesis comes directly from inspection of the wiring of animal bodies, that

looks for all the world *AS IF* it were a representationalist system! It

may not be, but until the strong contradictory evidence comes in, that *IS*

the most *REASONABLE* initial assumption!

Now, the Gibsonian / O'Regan / direct percepton concept, on the other hand,

has *NEVER* been demonstrated in ANY kind of artificial system, and there

is very good reason to believe that the whole concept is totally incoherent

and impossible *IN PRINCIPLE*!

How would you even build a robot that works by direct perception??? Would

you equip it with video cameras for eyes? If so, what do you do with the

data generated by those cameras? You can't send it to the brain, because

that would be computation and representation again, so we can save

ourselves the expense of video cable and computer brain. But what would

drive the servo-actuators? Where does that signal come from? And how does

the direct-perception robot project its experience out of its body into the

world so as to produce behavior *as if* it were actually *seeing* that

environment *without* representations and computations???

HOW WOULD IT BE DONE????

The concept is so vague as to be totally meaningless! Gibson himself

refused to discuss what gets sent from the eye to the brain, or what kind

of computations might occur in the brain. In fact Gibson even denied that

the retina records anything like an image! But he NEVER OFFERED ANY

ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATION for how behavior works besides a few vague

mumblings about being tuned to invariants in the environment. Gibson spoke

as if the computation of perception occurs OUT IN THE WORLD, rather than in

the brain. But there is no computational or representational *machinery*

out in the world, the only machinery is found in the brain, right where the

sensory nerves terminate, exactly AS IF the sensory organs were sending

data to the brain for processing!

As for O'Regans concept of using the external environment as a

representation of itself, that idea is DEMONSTRABLY FALSE, because probing

the world with visual saccades, especially in the monocular case, is

**nothing like** accessing a memory, internal or external, because every

saccade presents only a two-dimensional pattern of light. The three-

dimensional spatial information of the external world is **by no means**

immediately available from glimpses of the world, but requires **the most

sophisticated** and **as-yet undiscovered** algorithm to decipher that

spatial information from the retinal input.

Secondly, O'Regan's concept of direct perception is totally inconsistent

with the *phenomenal experience* of vision, where we do in fact experience

the world as a spatial structure, and we perceive individual saccades to be

located at the location in the global framework of space that we perceive

that saccade to be located.

Thirdly, the absurdity of O'Regan's concept is highlighted by the condition

of *visual agnosia* (specifically, *apperceptive* agnosia) which is a

visual integration failure. An agnosic patient can see individual features,

but cannot distinguish a picture of a bicycle from a picture of

disassembled *parts* of a bicycle. They can see a wheel here, and a wheel

again, but they cannot tell whether the second wheel is not just a second

glance at the first wheel, or if it is a separate wheel, they cannot see

the spatial relation between the two wheels. In fact, the experience of

visual agnosia is *exactly as if* vision worked as O'Regan proposes, with

individual glances picking out features in the world in the absence of a

global framework or spatial representation to store or record those

features.

The condition of apperceptive agnosia is the absence of a visual function

whose existence O'Regan effectively denies!

So don't be complaining about the vagueness of terms like information,

representation, and processing. Those terms are **perfectly clear**, and

are demonstrable in **actual physical robots** that receive sensory input

and compute behavioral responses.

Instead, the real concern is the vagueness of terms like "active

interaction with the environment" and "responsive to invariants in the

environment" IF NOT by way of sensory input and internal representations.

What does that even ***MEAN***?

Until the *principle* of direct perception is demonstrated in a simple

robotic model, the concept is totally incoherent and ill-defined!

Steve Lehar

I have been lurking in the recent discussion but I want to say that,

modulo a few excess asterisks, Steve Lehar's message on

anti-representationalism seems to me to be exactly right. Theorists

who present themselves as denying the existence of representations

almost always, on closer inspection, turn out to be denying that

certain kinds of representations exist (Brooks) or to be denying that

representations are as plentiful or play as big a role as the

tradition would have it (O'Regan, Noe, Clark), or whatever. Some just

refuse to talk about central issues at all (Gibson). Mounting a

flat-out denial that there is anything in the brain that stands for,

indexes, refers to, even pictures items other than itself is a pretty

tough task. (Actually, Lehar might be a bit hard on O'Regan on this

score, though some of his rhetoric invites Lehar's kind of response.)

Andrew

I think the argument against representation should be made based on

physics. Namely, what is the nature of the environment-organism

interaction allowing the brain to make a copy of it, how exactly can a

copy of this environment be made? Is it a tape-like recording? A CD?

And despite its enormous capacity, can the brain really afford to hold

a copy of the entire universe together with whatever extra brain power

is needed to analyze it? Judging by nature's preference for parsimony,

the answer is no.

Andrew Brook >

Yes, I am more accustomed to debating people who contest the notion of

*spatial* representations in the brain, given that neurophysiology has

not (yet) found "pictures" in the brain. It threw me for a loop to

find people like Glen Sizemore who deny representationalism

altogether! Even the most ardent supporters of Gibson's theories

generally take care to disclaim his most radical views (Bruce & Green

1987 p. 190, 203-204, Pessoa et al. 1998, O'Regan 1992 p. 473)

although they present no viable alternative explanation to account for

our experience of the world beyond the sensory surface.

Many of Gibson's observations on environmental affordances and invariants

were very valuable and insightful, even from a representationalist

viewpoint. In fact, it was Gibson's refusal to discuss physiology and

computation that released him from the burden of having to consider issues

of "neural plausibility", and that is why he dared to make such bold and

generally valid observations on the nature of perception.

But Gibson's profound epistemological error backed him into a corner which

is ultimately indefensible, which made him get defensive and dogmatic in

his later years, as often happens to those who commit themselves to

defending the indefensible.

Carreno >

I am viscerally sympathetic with this argument. Given what we know about

neurophysiology, it seems totally implausible that the brain could

construct a model of the world as rich and complex as our experience of it,

and maintain it in real time as we move about in the world. Carreno is

right: that does ideed stretch credulity to its elastic limit. But before

deploying Occam's razor we must first balance the scales, and take a full

accounting of the alternatives under consideration. For the alternative is

that we experience the world directly, as if bypassing the causal chain of

sensory processing. As incredible as representationalism might seem, the

alternative is even more incredible.

Lehar >

Fallacy of the excluded middle. There are other options. One is the

one I sketched in the message from which Steve quotes: that our

representations give us access to the world itself, not just to the

end point of the representing process. Our brain has the capacity to

work its way down the causal chain to experience the kickoff

point. How we can do this is a wonderful mystery but that we do it

seems, to me at least, pretty much beyond question. When I open my

eyes, I see the world around me. This is to be in epistemic contact --

to see, know, experience, be conscious of -- the world, the part of it

in my immediate vicinity anyway, not any representation or construct

of mine.

Brook >

Wonderful mystery indeed! Downright *miraculous*, wouldn't you say?

I mean, how would you demonstrate this in a simple robot model?

Experience or awareness of an object means having posession of

information about that object, color, shape, location, etc. Exactly

*as if* one had a miniature colored model of the object right there

inside your brain. Except we *DON'T* ?

So how would this work in a robot model? The video camera picks up a

2-D image which is sent to the computer brain, that extracts a few

features and performs a few computations, and suddenly, miraculously,

a three- dimensional colored data structure appears--not in the

computer brain in some kind of holographic 3-D imaging mechanism at

the end of the causal chain, but right back out there in the world!

With NO high-tech holographic imaging machinery involved!!! The image

just appears out there, disconnected computationally from any of the

hardware of the robot.

And when the robot closes its lens covers, the model out there

DISAPPEARS! As if it were causally connected to the computational

hardware downstream of the video signal, except it *ISN'T!*

I say again: Until the *principle* of direct percepton can be

demonstrated in an artificial sensory system, the whole idea is

completely implausible and ill-defined. I don't mean anything fancy,

just a simple demo like the representationalist robot. *HOW* does the

robot "work its way down the causal chain to experience the kickoff

point" ???

Steve,

I'm not sure what's going on here. We should be on the same side. Here

is why I think that some form of direct realism is virtually

unrejectable. When I open my eyes, I see a chair just as directly as

when I kick it, I kick a chair. In both cases, it is the chair that I

am in contact with. In neither case am I in (interesting, relevant)

contact with any intermediary. And -- here is why the view is

essentially unrejectable -- if you say, in either case, 'the contact

is not direct', then I will invite you to tell me what you mean by

'direct'? What could be more direct than seeing or kicking an object

in plain view in front of me? If this is not direct, what would be?

Simple robot model? I sketched how at the end of my message. In the

same way that vision systems since Marr's have been able to extract

three dimensional objects from two dimensional arrays, our vision

system not only extracts threre dimensional objects but allows us

'reverse infer' down the causal chain to be directly aware of

them. What more do you want?

Brook >

Yeah, thats what *I* thought when you chimed in to reject the extreme

Gibsonian (Sidemorian) version of direct perception! I guess that this

issue is not a clean binary choice, but there are a number of

intermediate positions between direct perception and

representationalism.

Brook >

Ok, stand in front of a chair, and before you kick it, touch your

finger to one eyeball (through the eye lid) and push it gently to one

side, until you see a double image. Now KICK! Now you see TWO chairs,

and TWO feet kicking them! Which one is the "real" chair and the

"real" foot? And what is the actual objective location of that chair?

If this is not IN-direct, what would be?

Brook >

Au contraire! Marr's vision model is entirely representational. From the

moment the image registers on the (synthetic) retina, all computational

processing of that image occurs inside the computer, or inside a brain.

Nothing gets projected out into the world again! There is *NO* "reverse

inference" going on here, but a feed-forward progression of *forward*

inference, from input stimulus to internal mental model. The computer never

has access to *any* information that is not explicitly represented in the

machine. That is an indirect representational algorithm!

Steven Lehar

Yet I could nowhere find a clear statement of what Gibson's "profound

epistemological error" is presumed to be.

For sure, Gibson avoided questions of mechanism. But that hardly seems

to be an epistemological error.

I am quite sure that Gibson understood the physics and biology, and

recognized that stimulation of retinal cells and the transmission of

signals on the optic nerve were part of the causal processes involved

in that direct perception.

Rickert >

For a summary of the epistemological issue and the various alternatives, see

Direct perception embodies a profound epistemological error.

Rickert >

Actually, Gibson made his views on the role of the retina perfectly clear,

and they were very much at odds with the consensus view on it.

Gibson, J. J. (1966) The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin.

p. 263:

The reason why Gibson denied that the retina records an image and

transmits it to the brain, is that to even allow this much

representationalism in the visual process is to acknowledge that the

principle behind representationalism is perfectly feasable, and that

the first stage of visual processing is apparently representational.

Steve Lehar said (among much else):

I respond:

Try another way:

Steve:

Me:

Steve:

Me:

Andrew

Ok, we've been round and round the direct perception v.s.

representationalism debate enough times to see that nobody is about to

change their minds, no matter HOW eloquent or persuasive the arguments

are on either side. Why is this so?

This is a sure sign of a *paradigm* debate!

As Kuhn explained, (Kuhn 1970 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions)

there is a profound difference between theories and paradigms, and how

to debate them. The problem is that what we are debating is not a

question of theory, like the question of whether the representation in

the brain is digital or analog, or whether time-to-collision

information is available from the optic array, which would be resolved

by the normal rules of logic and evidence. But in this case what we

are debating are the *foundational assumptions* with which we come to

the debate in the first place. Debates between paradigms tend to go

round and round in futile circles, because the participants are

debating from different foundational assumptions. We take our

foundational assumptions as a *given*, as obviously self-evident

*fact*, and from that perspective the opposing paradigm appears

patently absurd, it makes us wonder how intelligent, educated people

could possibly defend such an absurd and indefensible view.

But if alternative paradigms are to be fairly evaluated, it is

necessary to temporarily and provisionally suspend one's own

paradigmatic assumptions, (a feat that many find impossible to do) and

accept the assumptions of the alternative paradigm **as if they could

actually be true**. Only then can the competing paradigms be fairly

compared, not on the basis of the perceived incredibility of their

initial assumptions, but on the overall coherence and self-consistency

of the world view that they implicate in total.

In the case of our debate, we hear some state that it is "obvious"

that we experience things directly, while others state that it is

"obvious" that perception is indirect. If we begin with either of

those assumptions, we are sure never to reach agreement. In the case

of the historical debate between an earth-centered or sun-centered

cosmos, the earth-centered people argued that the idea of the whole

earth with all its mountains and forests and oceans spinning and

flying through space is so absurd and incredible on the face of it,

that it does not matter what evidence you might cite, they would never

be convinced!

There is a parallel with the current discussion, because as in that

ancient debate, there is a certain asymmetry in the two views: one

alternative is the "naive" view, in the sense that that is the view

that we adopt by default, even before giving the question any serious

thought, while the other view appears initially to be patently absurd.

In paradigmatic debates, the argument that one view "seems incredible" is

no valid argument. Many of the greatest discoveries of science seemed

initially to be so incredible that it took decades or even centuries before

they were generally accepted. But accepted they were, eventually. And the

reason why they were accepted was not because they had become any less

incredible. Facts such as the immensity of the universe, and its

cataclysmic genesis from a singularity in space and time, as well as the

smallness of the atom, or the bizarre properties of quantum phenomena, are

just as incredible today as they were when they were first discovered. And

yet all of these incredible theories have taken their place in the realm of

accepted scientific knowledge, not because they have become any less

incredible since they were first proposed, but because the evidence for

them has been irrefutable. In science, irrefutable evidence triumphs over

incredibility, and this is exactly what gives science the power to discover

unexpected or incredible truth.

There is an asymmetry in this debate: all representationalists were once

naive realists, whereas most direct perceptionists have never been

representationalists. I can tell you that I find representationalism **just

as incredible** as any of you do. It is absolutely incredible that my

physical skull should be larger than the dome of the sky. And it is

incredible that the brain can construct and maintain a real-time volumetric

moving image of the world with the rich detail and fidelity of the world I

see around me. Given current knowledge of neurophysiology, that appears to

be absolutely incredible!

But before we deploy Occam's Razor, we must first balance the scales and

take a full accounting of the alternatives under consideration. For the

alternative is that we can somehow become aware of objects and surfaces in

the external world *without* the mediation of sensory processing and

internal representations. That, in my view, is not just incredible, it is

incoherent, as demonstrated by the fact that nobody has ever, or could ever

possibly build a robot that can demonstrate the *principle* behind direct

perception in a simple model.

I am therefore suspicious of direct perceptionists who focus exclusively on

the incredible aspects of representationalism, without also acknowledging

the incredible aspects of direct perception. I can accept someone who

argues that both views appear incredible, but that they consider this view

to be somewhat less incredible than that one. That is a valid and

reasonable position. But anyone who does not see the profound problems in

direct perception (as I see the profound problems in representationalism)

is suspect of being a paradigmatic partisan, that they accept one view as

plainly obvious, thus requiring no further proof, while the other appears

patently absurd no matter what the evidence. One suspects of such people

that they never really understood the alternative position enough to give

it any serious consideration.

To those people I implore that they entertain the *possibility* that they

may perhaps be mistaken.

-William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act I, Scene 5.

Steve Lehar

Steven Lehar

Steven perhaps sees this as a problem. I don't. While I tilt toward

the direct perception side, I am not all all concerned that Steven and

Alex are strongly committed to representationalism. We don't need to

put all of our eggs in the one basket. Science is best served when a

problem is studied from several different perspectives. And may the

best perspective (whichever that is) win.

I don't think I agree with Steven's assessment.

No doubt naive realism is pretty much the received view. But direct

perception is not the same thing as naive realism. I suspect that if

people with an ordinary science education were asked to choose

between Gibson's account of vision and Marr's account of vision, most

would prefer Marr's account. So the default view would be closer to

that of the representationalists than to that of the direct

perceptionists. There are subtleties to Gibson's theory that make it

a little difficult to appreciate.

However, that is not the alternative. It seems that Steven can only

see one side of the paradigm shift.

The alternative, or one alternative, is that we can become aware of

objects and surfaces *with* the mediation of sensory processing, but

*without* the mediation of internal representations.

Incidently, I don't doubt that some of our interactions with the

world are mediated by internal representations.

-NWR

Reply to Neil Rickert:

Rickert>

Are you serious? It does not bother you in the least that people believe

two mutually contradictory theories of perception? Surely the goal of

science is to discover which of those two views is right, and which is

wrong. I am passionately interested in that question!

slehar >>

Rickert >

And exactly *HOW* would this be implemented in a simple robotic model? How

can a robot "become aware" (aquire immediate parallel access) to

environmental information *without* the mediation of internal

representations?

We hear these *words* loud and clear, but the *concept* behind the words

remains as clear as mud. Again, until you can demonstrate the *principle*

behind direct perception in a simple model, this concept is so vague as to

be virtually meaningless.

Given my comments at the launching of this "Theories v.s. Paradigms"

thread, isn't it perfectly clear what is happening here?

Isn't it perfectly clear that Rickert himself does not have a clear idea of

what he means by direct perception, or at least not clear enough to tell us

how to build the robot to demonstrate the principle. And yet he is

strangely blind to this gaping hole in his concept of perception. He

appears to be strangely blind to the profound problems inherent in the

concept of direct perception, he does not even acknowledge that any kind of

problem exists.

Indeed, Rickert exhibits all the signs of a paradigmatic partisan. He is

arguing from the initial assumption that perception is direct, but he is

unable to question that initial assumption itself. To him that assumption

appears so manifestly obvious that it requires no explanation.

I believe that the whole notion of direct perception is an elaborate

rationalization to try to make some kind of logical sense out of the

profoundly paradoxical observation that experience is outside of our head,

as if in the world itself, and yet vision is clearly representational, from

the retina on in to the brain.

But at a very deep level there is one small part of Rickert's mind that is

aware of this paradox, although his conscious mind is in denial over that

recognition. So, like Gibson, his response is to get more dogmatic and

emphatic about his certainty that his view is right, even though he cannot

explain it to us in any kind of detail, all he can do is to emphasize again

and again that you can perceive the world directly without representations.

Until Rickert can find it in himself to acknowledge the *problem* that we

are discussing, that is, the difficulty of actually implementing direct

perception as he conceives it, further debate is simply useless, because we

are arguing from different foundational assumptions. Rickert BEGINS with

the assumption that perception is direct, so he cannot contemplate the

possibility that it might not be.

Steve

Steve Lahar represents direct realism, a position I hold, this way:

But that is not my view at all!!!! As I have said over and over and

.... OVER! (The caps may get me censored.) Nor, given that it is an

utterly implausible view, is it the view of most other direct

realists. A rough approximation of my view would be:

Furthermore, I don't think the difference between us is a paradigm

shift difference, I think it is a difference induced by an implacable

belief, totally untouchable by evidence or argument, that *if* there

is a medium of perception, *then* the resulting perceptions cannot be

direct. To which I respond:

You can define the word *direct* this way if you want, but if you

define it as it is usually defined, that we are aware of objects

around us, not just end-products of sensory processing in our brains,

then the inference needs argument and evidence to support it. And we

have seen not a single bit that the direct realists in the crowd have

not been able to deal with handily.

Andrew

Lehar >>

Brook >

Well in that case you are not the target of that criticism.

Brook >

And exactly *HOW* would that occur??? If you cannot explain how this

concept might be implemented in an artificial robot, then the idea is

so vague as to be *meaningless*! Simply stating "over and over and

.... OVER!" that perception is direct is just not going to cut it!

Steve

Lehar:

Sizemore:

I agree with Glen as against Steve on which view comes first. Though I

agree with Steve that some kind of inchoate realism would seem true to

most people who have never studied cognition, I was thoroughly

indoctrinated in indirect representationalism in school as though it was

the obvious and even the only conceivable point of view (Steve?). It

then took me years to battle my way out of that bewitchment and back to

a view that allowed me to accept what seems to me obviously true -- that

I see, touch, taste, feel, and smell things other than myself,

especially including other people. One good name for my view (he said

being deliberately provocative) would be: direct representationalism.

Which comes first? When we are children we begin with the most naive of

naive realism--that the world of experience is the world itself, viewed

directly where it lies.

Then we learn about the eye with retina and optic nerve that project to the

brain, an obviously representational system. At this point our mental image

of the problem goes into a bistable state. We understand the causal chain

of vision, but at the same time we observe that the experience, from the

end of the causal chain, jumps back out of your head again and appears back

out in the world, "like a stretched rope when it snaps", as Bertrand

Russell expressed it. This is the state in which direct realists become

permanently stuck.

Andrew Brook>

A very apt name for a befuddled epistemology! Experience is both at the end

of the causal chain, and it is also back out at its beginning. Vision is

obviously representational, at least as far as the retina (except for

extremists like Gibson and Sizemore) and yet at the same time perception is

direct, as if bypassing the retina and viewing the world directly again.

Paradoxically, both appear to be true simultaneously. "Direct

representationalism" indeed!

It is only by really taking representationalism seriously that the

epistemological paradox is resolved, although that comes at the cost of an

almost *incredible* neurophysiological hypothesis, that the brain is

capable of constructing a three-dimensional volumetric real-time moving

model of the external world with as much rich spatial detail as you see in

the world around you.

Even if you continue to find that hypothesis too incredible to swallow,

will you not at least admit the profound paradox inherent in the direct

perception view? As I said in the "Theories v.s. Paradigms" thread, if you

cannot even see that there is a paradox at all, then further debate is

really a waste of time.

We've beaten this direct perception v.s. representationalism debate nearly

to death, without much progress. And yet one view is right, and the other

is wrong. One day the conclusive evidence will come in that will finally

settle the issue once and for all. Maybe even in our own lifetimes! That

raises the question:

What would it take to convince you? What kind of evidence can you possibly

imagine that would settle the issue finally and conclusively? Or are we all

so dogmatic that we will go to our graves in obstinate denial no matter

what the evidence?

Just for the fun of it, let me hypotheticalize two alternative future

scenarios that once and for all *PROVE* the correctness of

representationalism, and of direct perception, respectively. Would the

paradigmatic partizans among us be convinced by these? I suspect the

responses might be illuminating.

H1: REPRESENTATIONALISM IS PROVEN!

It is discovered in the future that the brain is one giant resonator, just

humming with one global resonance through all its tissues, right down to

the spinal cord. This sets up volumetric spatial standing waves in the

various cortical areas, in patterns like three-dimensional Chladni figures.

Although the different cortical areas are connected, they are also

independent resonators, each one sustaining its own spatial standing wave,

as in a separate Chladni plate. And yet they are also coupled, so that the

pattern in one cortical area is coupled to the patterns in all the other

areas. If you modulate the resonance in one area, it has an influence on

the pattern in all the other areas simultaneously. This immediate parallel

coupling between resonating areas turns out to be the solution to

the "binding problem". If you *were* the standing wave in your brain (which

in fact you *are*), there would be no way for you to tell that your

resonance is distributed over different resonators, because the pattern of

your resonance would be unified.

Careful neurophysiological recordings reveal that the experience of

volumetric substance and void, solid matter surrounded by empty space, is

encoded by the *phase* of the vibration: positive phase within perceived

objects, and negative phase in the surrounding void. Experienced colors

correlate with a cylic phase representation (as in the NTSC color

television standard, for those who are familiar) which finally explains why

phenomenal color defines a circular space (the color circle) even though

the spectrum is linear. When a subject views a three-dimensional scene,

neurophysiologists can sample that volumetric experience in various parts

of the visual cortex, and actually "read" what the subject is experiencing

in any portion of his visual space by the resonance in that part of his

cortex.

When a person turns their head, or moves about in the world, the spatial

image in each of the cortical areas rotates and translates in synchrony,

like the images in an array of television sets in a shop display that are

all tuned to the same channel.

If the mapping of experience in the brain were decoded so that *every

aspect* of experience could be deciphered from the outside with appropriate

probes, which revealed a complete world of experience all encoded inside

your brain, and if neurophysiologists could transmit signals into the

visual cortex and predictably cause the subject to experience a red square,

or a blue circle, or whatever, by using the right Fourier code, would THAT

be sufficient to finally convince the doubting direct perceptionists out

there?

I suspect not.

Ok, then lets switch to hypotheticalization #2

H2: DIRECT PERCEPTION IS PROVEN!

Uh, here I have a little more difficulty imagining the "experimentum

crucis" (Oops! My paradigmatic partizanship is showing!) But lets give it

a try regardless.

In the future it is discovered that there are in fact NO representations in

the brain! Even the image on the retina is not really an image as such,

transmitted from the eye to the brain, but instead, the eye is a tool for

active exploration of the environment that detects environmental

invariances OUT IN THE WORLD where the objects of perception reside.

This bizarre notion is finally proven beyond a shadow of doubt with the

invention of the "experience meter", a device tuned to some quantum-

mechanical cat-in-the-box state of existence in the world, so that it can

detect when a material object is being experienced by someone. If you point

the experience meter at an object in front of a person, the meter lights up

when that person's eyes are open, and blinks out when their eyes are closed.

The meter has a screen that shows the information content of the subject's

experience--monochrome for people who are color blind, full color for

people with normal vision. When a subject with visual agnosia views an

object, the experience meter displays a chaotic jumble of ever shifting

visual features instead of a coherent image. There is a peculiar void, or

loss of signal from the rear faces of objects that are not exposed to the

subject's direct view, as well as for background objects that are occluded

by foreground objects. This finally proves that experience is not some

mysterious non-existent entity, but a real physically measurable quantity

that exists out in the physical world, not in a person's brain.

The experience meter also records *affordances*. When a subject views a

chair, there is a measurable "sit-onable" affordance detected that appears

superimposed on the chair, and that affordance has the mysterious property

that it has a causal influence on the subject's motor system, so as to tend

(when circumstances are right) to make the subject actually move toward the

chair and attempt to sit on it. Furniture manufacturers use the experience

meter to objectively measure the "sit-onable" appeal of various furniture

designs. Neurophysiologists map out in exquisite detail the relation

between the measured affordances, and the spatial influence that they exert

on the various muscles of the body, by some kind of mysterious action-at-a-

distance from the affordance out in the world, to the muscles inside the

body.

Would THAT be sufficient to finally convince the doubting

representationalists out there?

I gotta say, *I* would be convinced!

Would you?

Steve

Steve, absolutely the right approach, ingeniously carried out. Trouble

is, it does not address the issue between, for example, you and me. I

can't imagine anything that would 'prove' direct perception *as you

describe it*, anything compatible with what we now know about the brain,

anyway. But within representationalism, there are two houses.

There is the house of those who think 'If a representational medium is

present, the results can only be indirect perception/consciousness.'

And there is the house of those who think, 'The right kind of

representational medium lets us go right through it all the way to the

world itself, so that the result is direct perception/consciousness.'

For me, this debate between direct and indirect representationalists,

which is within representationalism, is the interesting one.

Andrew

Andrew Brook >

[1]:

[2]:

Well then can you imagine the "experimentum crucis" that would select

between THOSE two alternatives?

If not, then what does the second alternative actually *mean*?

Lehar has conflated conceptual and empirical issues. The only slight

difference is that he considers future experiments, whereas most

cognitivists claim that representationalism has already been

proven. Once again, the notion that psychological phenomena require

current representations and stored and retrieved representations (as

well as a host of related notions like expectation, unconscious

inference, unconscious rule-following, etc. etc.) for their

explanation is an assumption, as is the view that they do not.

As long as these views remain assumptions, and it is not clear that

they can ever be anything else, philosophical debate and conceptual

analysis is the only avenue via which they can be compared. Did Lehar

not, in fact, argue this himself when he invoked Kuhn a couple of days

ago?

No one has this stuff worked out by any conceivable stretch of the

imagination, but, quite bluntly, the representationalists think that

they do and this faith is, I assert, largely a product of the

ubiquitous, literal, usage of real representations such as photographs

and paintings etc. It is bewitchment by metaphor.

But even paradigmatic issues can be determined by experiment, at least in

principle. The earth-centered cosmos has now been conclusively rejected by

the "experiment" of flying around the back side of the moon without

colliding with the crystal sphere that supposedly supports it in space.

Although this experiment was technologically not feasable in Ptolomy's

time, Ptolomy and Copernicus could have predicted the different outcomes

of this "experimentum crucis" based on the two theories.

Any "theory" that is *NOT* testable by any experiment, even in principle,

is not a scientific theory at all, but a pure *belief*. For example the

existence of immaterial souls, if they are by definition undetectable by

physical means.

If you cannot describe an experiement that could prove direct perception at

least *in principle* with some kind of future technology, then direct

perception is a *belief* not a theory, since it predicts nothing different

than the alternative representationalist hypothesis.

But the truth is that the principle of representationalism *is*

demonstrable in a simple robotic system, while the principle of direct

perception remains as mysterious as the immaterial soul! After all these

rounds of debate, we still have no idea how such a system could possibly be

built in a real physical system.

Steve

Lehar >

...If the mapping of experience in the brain were decoded so that *every

aspect* of experience could be deciphered from the outside with appropriate

probes, which revealed a complete world of experience all encoded inside

your brain ... would THAT be sufficient to finally convince the doubting

direct perceptionists out there?

I suspect not.

You are right. That would not convince me.

Lehar >

[some of the details snipped]

This bizarre notion is finally proven beyond a shadow of doubt with the

invention of the "experience meter", a device tuned to some quantum-

mechanical cat-in-the-box state of existence in the world, so that it can

detect when a material object is being experienced by someone. If you point

the experience meter at an object in front of a person, the meter lights up

when that person's eyes are open, and blinks out when their eyes are closed.

This would convince me that I should consult

the Amazing Randi, so

that he can uncover and debunk the trickery involved in the

demonstration.

The trouble with Steven's two examples is that they are both

quite implausible. They look like sleight of hand parlor tricks.

A scientist needs better evidence than that.

To convince me, I need a detailed account of the relevant processes.

This should, preferably, be at the level of information processing.

It should plausibly account for all of the unresolved questions. And

it should be supported by empirical evidence.

-NWR

Neil Rickert >

Well then is there *ANY* possible future experiment that would prove it to

your satisfaction? If not, then you are a hopeless paradigmatic partisan.

Rickert >

What *kind* of evidence are you talking about? Describe the experiment!

Rickert >

Notice that the direct perceptionists are always long on high sounding

verbiage and vague concepts, but very short on specific mechanisms and

mechanical details.

They cannot describe a simple robotic system that would demonstrate the

*principle* of direct perception in an actual physical system, and they

cannot describe a future experiment that would prove it one way or another.

All this just confirms my original suspicion that the concept of direct

perception is no *theory* at all, but merely a series of vague

rationalizations used to justify their naive realist intuitions. It is

impossible to pin them down on *any* kind of specifics.

Steve

Lehar:

Sizemore:

Lehar:

Sizemore:

Lehar:

Sizemore: Yes. Whether or not there are representations that are

stored and retrieved etc. etc. are [not] beliefs, they are

assumptions.

Lehar:

Sizemore:

An alternative view is that perception is behavior, and that

behavioral function is mediated by physiology. Unless all "mediation"

is "representation" (and I argue it is not) this simple statement

constitutes the beginning of a scientific approach. You are correct

that "we still have no idea how such a system could possibly be built

in a real physical system," and we have representationalism to thank

for the wild-goose chase that constitutes much of "cognitive

neuroscience." We understand, in some complete sense, behavior at

about the level of habituation of the gill-withdrawal reflex in

Aplysia, and maybe some classical conditioning of the system (and

despite the language that Kandel uses, there is little to be called

"representation" here, unless everything orderly is

representation). Little wonder that "we still have no idea how such a

system could possibly be built in a real physical system," if the

system in question is the behavior we call seeing and hearing etc.,

and the other behavior of which it is a part. We know some of the

behavioral observations that need to be explained, at least to the

extent that some portions of psychology actually demonstrate

behavioral regularities in individual subjects, but we do not yet know

how physiology mediates such behavior. But to depend on the obviously

category-error-ridden conceptual muddle that constitutes

representationalism is no solution.

The question whether psychological phenomena require internal

representations is not just a conceptual question, as Sizemore

suggests, it is also an empirical question that will one day be

confirmed one way or the other experimentally, as soon as we figure

out the code of the brain. Because the theory of direct perception

states that there is no need for internal representations, or in the

softer version defended by Andrew Brook, the internal representations

do not need to encode ALL of the information of experience, because

SOME of that information can be perceived directly *through* the

representation (whatever that means). In any case, if it is discovered

that the brain actually *does* explicitly encode *ALL* of the

information in our experience, that will pretty much prove direct

perception to be false.

Of course there will still be dogmatic defenders of direct perception even

after that discovery, such as Glen Sizemore who tells us that he would not

be convinced even if representations *are* found in the brain, because we

would still not understand how we *see* those representations. (But then

neither does Direct Perception tell us how we can *see* the world *without*

representations, so the mystery of experience remains regardless.)

But you can never convince *everyone*. After all, there are still people

who believe in God and intelligent design, as opposed to evolution, despite

the overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

The *only* kind of paradigm that remains purely conceptual, in Sizemore's

usage, are theories that make no testable predictions whatsoever. For

example a version of direct perception that posits that there *are*

complete and explicit representations in the brain that encode *all* the

information of experience, but that perception is still direct, and does

not actually *use* those representations. Or the theory that God did design

the world, but that he used evolution has his mechanism of creation. Those

kinds of theories are indeed purely conceptual, not at all empirical,

because the experimental evidence is identical for both alternatives. But

such theories are not theories at all, they are *beliefs*, and thus fall

outside the realm of science.

Steve

The question of Conceptual v.s. Empirical issues raises a question about

Andrew Brook's softer concept of direct perception *through*

representations.

Question to Andrew Brooks:

Is there *any* information in our experience that is *not* explicitly

represented in the brain? Like the information about the world that is

experienced *through* the representation instead of *in* it? If so, then

your concept of direct perception *through* representations could be tested

in principle by seeing whether that information is in fact encoded in the

brain or not.

If on the other hand you posit that *all* of the information in our

experience *is* explicitly encoded in the brain, but we still view the

world "directly" *through* that representation, then we are in perfect

agreement, that in veridical (non-illusory) perception we are viewing the

world "directly" in that sense. But in that case your theory becomes

indistinguishable from represntationalism. (Viewing "directly" *through* a

representation strikes me as a contradiction in terms.)

Steve

Maybe this will help situate my position. I agree with Glen Sizemore that what

is between us is mainly conceptual, not empirical. Another way to put this is

that we are not disagreeing about the facts of human information processing and

behaviour, we are disagreeing about how these facts should be interpreted, what

they entail for theory.

It is hard to tell whether your "direct representationist" position really

is conceptual, or whether it has empirical implications. It is very

slippery the way you describe it. But in any case, if it *is* purely

conceptual, and makes no predictions, then it is entirely vacuous. It is

like saying that "the representation is so good, it really feels as if I am

seeing the world directly". Well we all agree with that! But if your theory

does not make any predictions, then it is no theory at all! It is a belief,

and a rather vague and ill-definable one at that.

Glen Sizemore calls them "assumptions" rather than "beliefs". But the issue

is what are they assumptions about? If they are *untestable* assumptions,

such as the existence of immaterial souls, then they are not scientific

assumptions at all. If they *are* scientific assumptions they *must* make

some kind of predictions, even if they are only testable in principle.

In fact there is a very profound empirical issue that is wrapped up in this

debate, and that is the question of how one would construct a robot that

operates by the same principle as our own brain. Either it needs to be

equipped with a representation of the world, or it needs to be designed to

extract that information from the world directly. And the debate also has

profound implications for neuroscience, that is, should we even be *looking

for* representations in the brain, and should we expect those

representations to encode *all* of our experience, or only part of it?

It is exactly the profound implications of this debate for artificial

intelligence, philosophy, and neuroscience, that make the epistemological

question interesting in the first place!

Steve,

if your theory/interpretation/whatever and mine are both

compatible with all the facts, they are *equally* untestable, at least

at the bar of the facts. As I said yesterday, I suspect that that is the

case.

Andrew

*IF* our theories are indeed both identical with respect to

predictions and future discovery of facts, then they are identical,

because you would claim, as I do, that every aspect of experience must

necessarily be explicitly encoded in the brain, and thus your theory

is indistinguishable from representationalism. Welcome to the most

reasonable explanation!

But then your rhetoric about seeing things directly, *through* the

representation amounts to no more than that the representation is so

damned convincing that it really *seems* as if we are viewing the

world directly, although you acknowledge that you are seeing it

"through" the representation, which is tantamount to saying that you

are seeing the representation, while having the vivid impression that

you see the world itself, as when watching through a television

monitor.

If on the other hand you continue to insist that seeing *through* the

representation is something different than observing the state of your

brain, while believing that you are seeing the world directly, then

you will have to explain what that actually *means* in real

down-to-earth terms with sufficient specificity that we would know how

to build a robot that sees directly by that same principle, or that we

could describe the experiment that would distinguish between the

two--for example that there is information encoded in the

representationalist view that is not encoded in the direct

representatioanlist view. We still do not know what you actually mean

by this term.

Doesn't it bother you to defend a view so adamantly and with such

conviction, while being unable to specify exactly what you mean by it? It

sure has me confused!

But then so do all the other attempts at rationalizing direct perception!

Steve

Steve,

1. Stop the aggressive bombast. I am not intimidated.

2. I have put a lot of effort into specifying my position in detail,

much more than you have put into specifying yours. That you either do

not understand what I am saying or do not believe that I could mean is

another matter.

Andrew

Brook >

I am sorry, the intent was not to intimidate, nor to belittle your

contribution. You have done a masterful job of articulating a very slippery

issue, and you have my deepest respect for your willingness to explain your

thinking very honestly and in excruciating detail. I am really very

interested to hear what you have to say.

My point was that I am truly baffled at how you perceive your own position.

You freely admit that you cannot describe a robot that operates by direct

perception, and that you cannot conceive of an experiment that would

differentiate between our two views. And now in the most recent exchange

you raise the level of ambiguity of your concept of direct perception one

more level by saying that you **don't know** whether your view suggests

that the representation in the brain encodes *all* of the information in

your experience or not. Given all that, can you understand my puzzlement

about exactly what it is you are proposing?

Contrast that with the powerful conviction and certainty with which you

argue your position, and it makes me wonder just what it is that you are so

powerfully certain *of*? As far as I can tell, you acknowledge *everything*

about representationalism, except for the one single statement that you

know for a fact that your experience is *direct*, *not* an experience of a

representation. Can you not see a contradiction here? The concept

of "direct representationalism" is a contradiction in terms, because

representationalism is by definition indirect, by way of a representation.

In all our long debate, I have never once heard you acknowledge this as any

kind of paradox. It need not be fatal; you might still argue that you

consider that paradox more tolerable than the incredible notion that the

whole world is represented in your head. That would be a reasonable and

understandable position. But do you not even see what we

representationalists see as a problem with your view?

And how can you maintain your view with such supreme conviction when you

cannot describe an experiment that would differentiate our views? Isn't it

in the very nature of scientific theories that they make predictions?

Shouldn't this at least dampen the magnitude of your conviction, or at

least your expectation that others be persuaded to join your faith? As I

explained earlier, I can see the profound problems in the

representationalist view, but in my view they are outweighed by the deeper

paradoxes of the direct perception view. But do you even see where we see a

problem in your position? Why do we not hear you at least acknowledge that

much?

Your arguments just confirm my initial suspicion that the theory of direct

perception is logically indefensible, but that people hold it with great

conviction simply because it *SEEMS* so obviously to be true, and the whole

theory of direct perception is just an elaborate rationalization of that

initial assumption. Can you disabuse me of that suspicion?

Brooks >

Really? Are you counting THIS?

and THIS?

and THIS?

I have invited you to read Chapter 1 of my book (available on-line) but I

have not hear your commentary on it. I would be interested to hear your

reaction to it. What do you make of the "introspective retrogression"? I

would really like to hear what you have to say.

Steve

Lehar:

Sizemore:

Lehar:

Sizemore >

Sizemore >

Whether or not something is a representation depends on whether somebody or

something uses it as a representation. A picture in a newspaper is only

representational when viewed as a depiction of something else, not when the

newspaper is used to line your bird cage. Voltages in a computer memory, or

patterns of activation in a retina, are not representations unless or until

some process further downstream interprets them as such, at which point

they become representations only to that process.

Sizemore >

The retina simply responds to light, it does not experience any kind of

representation, just its own state. Lower brain functions interpret the

signal from the retina as a pattern of light, like the meaningless patterns

in an abstract hallucination. The next higher brain functions interpret

those patterns of light as meaningless objects in an illuminated scene,

like the view of an abstract sculpture. The next higher levels interpret

the pattern of objects as a meaningful scene, for example a view of a face.

And the highest levels of brain function interpret the face as someone you

know, and call up the appropriate response such as nodding or greeting the

experienced person. Only the last stage involves the *whole* visual brain,

although not necessarily the auditory, olfactory, or limbic functions,

which may or may not engage in any particular experience. The lower level

functions do not involve the whole brain, and in fact there are an array of

visual deficits caused by failures of various regions of the brain (e.g.

visual agnosia) that clearly demonstrate that the whole brain does not

always have to be involved in every kind of experience.

And likewise in synthetic vision. An image on a photodiode array is just a

pattern of voltages, it does not represent anything until the video camera

is plugged into a computer that interprets that signal as a pattern of

light, or an image. Further algorithms work on that data on the assumption

that it is a pattern of light, to detect presumed features in the scene,

and then further algorithms work on that feature data to extract presumed

objects from that presumed scene. Those are all representations, whether or

not there is any correspondence between two domains. If the lens cover is

on, then there is no pattern of light, although the rest of the algorithm

mistakenly interprets the signal as an image of light nonetheless.

Sizemore >

The word "see" implies a viewer, and that does not apply inside the brain,

because the viewer is the whole brain. Instead, we experience the states of

our own brain, and when the whole brain directs its attention to an

external object (by way of its internal representations) then we call that

process "seeing". It is a fallacy to insist that experience necessarily

involves eyes and a separate viewer. But we've been over this ground once

before already.

Sizemore >

True enough, but it *is* a *testable* assumption, at least in principle,

and a good way to test it is by demonstration with a simple model system.

Representationalism is easy enough to demonstrate. Direct perception is

more difficult to demonstrate, because nobody has ever articulated the

concept with enough specificity to either build a model, or to make

predictions.

Ok, lets try the *ontological* approach to the Direct Perception

v.s. Representationalist debate. What is the ontology of experience?

First let us agree what we mean by experience. For example visual

experience is the colored three-dimensional volumetric world you see

around you when you open your eyes. This is distinct from the

objective external world in the fact that when you close your eyes,

the visual world disappears, or rather, it is transformed into a foggy

brownish space of indefinite extent, while the real world continues to

exist unaffected by the blinking of your eyes. Whether you are a

direct or indirect perception advocate, we can agree on the definition

of visual experience, even though representationalists believe it to

be located inside the brain, while direct perceptionists locate

experience out in the world beyond the retina.

In either case, visual experience takes the form of modulations of

color qualia across a volumetric space. For example a checkerboard

pattern is experienced as an alternating modulation of black and white

squares. What is the *ontology* of those alternating qualia? What is

it that flips from black to white and back again? We know that it is

an experience, and that experience is spatially extended in a

pictorial fashion, but is there anything in the external physical

world that corresponds to that experienced alternation? What is its

substance? Does it even have one?

The representationalist answer is that qualia are different states of

the physical brain, and thus they are located inside the brain. In

other words the brain must posess some continuous spatial medium

across which extends a pattern of alternating states. Whether these

states correleate with voltages, spiking frequencies, or some standing

wave representation, remains an open question at this point. But

experience has physical presence in the physical universe known to

science.

But what is the direct perceptionist's answer? What is the "stuff"

that changes color across space that you experience? And where is it

located? And is it in principle detectable by scientific means at that

location?

If my experience of a chess board is out there where the chessboard

exists, is the black and white pattern I experience the alternation of

the pigment in the paint on its surface, perceived directly? Or is it

the reflectivity of the surface experienced directly? Or is it the

intensity of reflected light experienced directly? Or is it a pattern

of activation in my retina? What is its ontology?

I think that direct perceptionists are uncertain about the ontology of

experience, they perceive it in a bistable manner, as being both an

external objective, and an internal subjective entity, and their

answers, when probed, flip back and forth between these two as if a

pattern in your brain could somehow be also outside of your head. The

whole concept of direct percption is founded on a profound

epistemological error, that we can in principle be conscious of things

which are not explicitly represented in our brain. Direct perception

states the *problem* of experience, it does not offer a *solution* to

it that can either guide the construction of a model of the concept,

or even an experiment to test the concept. The theory of direct

perception is every bit as mysterious as the property of consciousness

that it is supposed to explain.

The representationalist position is more coherent because it posits a

single ontology, that the modulations of the qualia of visual

experience are modulations of the physical state of your brain across

some spatial representational medium. And it makes the testable

prediction that that medium and its modulations will one day be

discovered and decoded in the brain. My vote is for a standing wave

representation using a Fourier code to produce moving volumetric

holographic images in the brain, and that those images correspond

directly to our experience.

Glen Sizemore will complain that there remains the problem of

experience, and why it is we have it when our brain is in certain

states. But if you accept that mind is a physical process taking place

in the physical mechanism of the brain, and you acknowledge that the

brain is conscious, then that already is an admission that a physical

process taking place in a physical system can under certain conditions

be conscious.

Besides, the mystery of experience, or why consciousness exists in the

brain, is by no means unique to representationalism. Direct perception

cannot resolve that one either. Representationalism at least offers an

account of the functional aspects of experience that can be expressed

in actual models and make testable predictions. Direct perception does

not even offer that much.

Steve

It's an ingenious argument. It seems that you could use that method

to prove that we don't eat food, we eat representations of food.

It makes you wonder how we get our nutrients.

You seems to be assuming the kind of Cartesian theater that Dennett

criticised. I don't agree with that. But even assuming a Cartesian

theater, you are misusing "experience". For example, my experience

in watching a movie includes my emotions and thought. It isn't just

what was played on the screen. Contrary to your assertion, I don't

locate experience out in the world. I don't consider it a thing. It

seems to me that treating experience as a thing is a category mistake.

The argument about blinking the eyes is interesting, because I think

that actually argues for direct perception. If there is some sort of

volumetric representation, then you would think your visual

experience would persist during a blink, perhaps slowly fading out.

May I suggest that the "foggy brownish space of indefinite extent" is

closer to what is represented.

SL >

There is no such stuff. You have confused the issue by your misuse

of "experience".

...

I seriously doubt that there is enough DNA in the human genome to

encode the hardware specifications that would be required for the

proposed system.

In another message ("Conceptual vs. Empirical Issues"), Steven wrote:

SL >

There is nothing explanatory about representationalism. Most

representationalists admit that they are unable to explain conscious

experience. The argument about an infinite regression of homunculuses

keeps coming up precisely because representationalism explains

nothing.

Whether a system uses direct perception, or is based on

representations, in an implementation issue, not an explanatory

issue. So lets stop the arguing, and wait for until there is enough

empirical evidence to answer questions about implementation details

in homo sapiens.

Rickert >

No, just that we experience internal representations of the

external "nouminal" food that nourishes us.

Rickert >

It seems there are a lot of these "category mistakes" in direct perception.

I see a spatial structure that is my experience, it is distinct from the

world itself, and yet we are not permitted to think of that spatial

structure as anything we can talk about. It seems that a lot of direct

perception involves prohibitions against certain concepts, as in

behaviorism, that fobade discussion of conscious experience. Curiously,

all of these forbidden concepts are the very things that reveal the

incoherency of direct perception.

Rickert >

I see. Because closing the eyelids makes the real world out there cease to

exist momentarily. Hmmmm...

Rickert >

No, you would expect it to blink out immediately when the input data stream

is blocked, like the image on a photodiode array when you put the lens

cover on.

Rickert >

There I believe you put your finger on what I believe is the principal

reason why representationalism is generally not given serious consideration.

Rickert >

Well it does explain the *functional* aspect of vision, that is, how the

information of the world gets in to the computational hardware of the

brain. Direct perception does not even explain that much. And direct

perception does not explain experience either, it merely prohibits

discussion of it.

Rickert >

I think that is wise. We are not making any further progress in

understanding each other. With this last ontological argument I have

expended my last big arrow from my quiver. I will provide a summary

overview of all the arguments we have covered in these various threads

under the Subject:

Summary: Direct Perception v.s. Representationalism

Steve

We have had a full and informative exchange on the question of

Direct Perception v.s. Representationalism, and it seems we have

pretty much exhausted that topic by now, as we are now just repeating

the same arguments over and over again. So I will bow out of the

discussion in a major way at this point, although I will answer any

residual questions that people might have. I have no more major

arguments to make on the subject. Most sincere thanks to all who

have contributed, and to all those lurkers out there who have found

this debate worth following. If nothing else, it is in my view a most

fascinating topic, and resolving this issue once and for all would be

of the greatest significance for philosophy, psychology, and

neuroscience. I hope we have advanced that cause if only by a small

notch.

I will take this opportunity to summarize the whole debate as I see it