Plato's Cave: Inverse Perspective Transformation

The Inverse Perspective Transformation

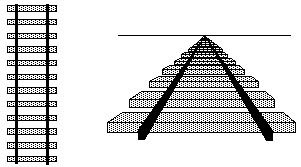

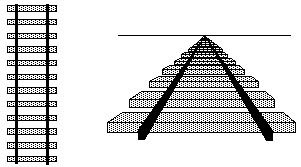

The laws of perspective transform the parallel rails of a railroad

track into converging lines that meet at the horizon. The job of the

visual system is to undo this transformation and to restore the

percept of parallel tracks, while giving the viewer information about

the angle from which those tracks are being viewed.

The architecture of the bubble world model has the property of

automatically performing this inverse perspective transformation.

Generally speaking, this is achieved by applying the same perspective

transformation to the infinite Euclidean grid or Cartesian coordinate

system, and then using this "bent ruler" as a measure of straightness

in the perspective-distorted world.

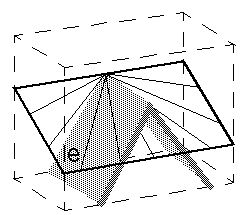

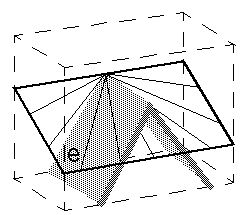

In particular, this is how it works. We begin by inverse-projecting

the image of the converging rails onto the front face of a slice of

the perceptual mechanism as described in the bubble model, which

produces an inverted "V" shaped "peaked roof" of influence through the

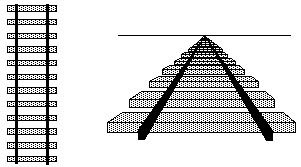

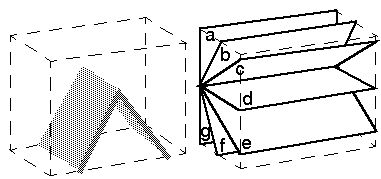

depth dimension as shown below. The difference in the bubble

world model is that the texture of neural connectivity, or

direction along which collinearity and coplanarity operations tend to

diffuse is no longer rectilinear, but follows a nonlinear pattern. In

particular, the back plane represents perceptual infinity. This block

of perceptual tissue therefore represents a rectangular slice from the

periphery of the perceptual sphere, viewed from the inside. In order

to describe the direction of this texture of connectivity within this

block, consider the set of planes a through

g below, which pass through a horizontal line at the

vertex of the inverted "V". Planes a and

g follow the back surface of the block, and thus

represent perceptual infinity, while plane d runs

horizontally, and passes through the "eye of the observer" at the

center of the perceptual sphere.

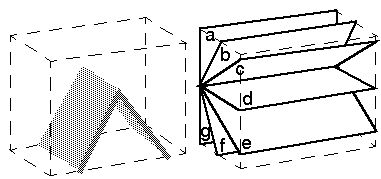

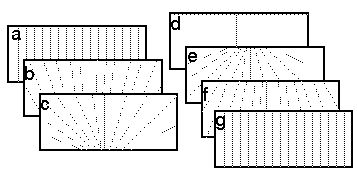

The figure below represents the texture of connectivity within each of

these planes, depicted as shown above, i.e. viewed from "below" for

planes a through c, and from "above"

for planes d through g. You can see

that the texture defines a set of converging lines, but the angle of

convergence varies from plane to plane.

These converging lines represent the expected texture of convergence

of parallel edges on a surface viewed from various angles. For

example, plane e represents the perspective view of a

horizontal plane as seen from slightly above, like a tiled floor

viewed in perspective, whereas plane f represents

that same horizontal plane viewed from a higher vantage point. Planes

b and c represent the view of a

surface from below, like an overhead tiled ceiling. Planes

a and g represent the extreme case

of a tiled wall seen at infinity, i.e. like a birds-eye view with no

perspective distortion, while plane d represents the

singularity of a plane viewed from within the plane, i.e. everything

is collapsed into a single horizon line.

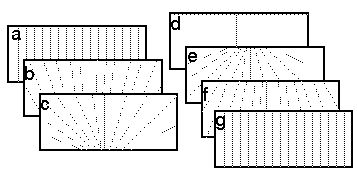

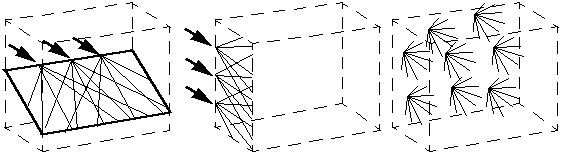

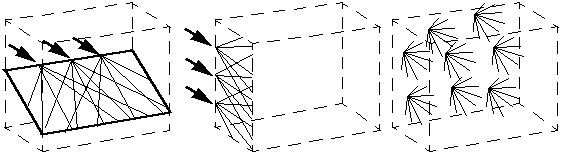

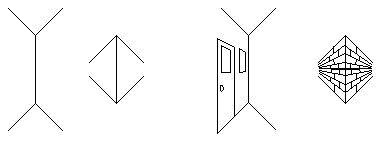

Now in fact this planar view of the connectivity in the perceptual

sphere is somewhat of a simplification, because horizontally within

each plane there are many such vanishing points, as suggested below

(left), and vertically there are many such sets of planes, as

suggested below (center), so the true situation is something like the

figure below (right), i.e. the external surface of the perceptual

sphere is a continuum of intersecting vanishing point vertices,

although it is to be remembered that this surface is actually

spherical, so the central axes of all of these vertices actually meet

at the center of the perceptual sphere. Each of these vertices

therefore represents the Cartesian grid rotated so that a major axis

passes through that point, and thus represents the perspective view of

that grid at that orientation as viewed from the origin.

Now that I have defined more precisely the connectivity architecture

of the perceptual sphere, it becomes clear how this architecture

automatically performs the inverse perspective transformation. For

when a pattern of converging lines is inverse-projected through this

structure, it will coincide with only one of these many sets

of converging lines. In our example, of all the multiple sets of

converging lines in the system, only those in plane e

match the angle of convergence of the rails in the image.

An interesting feature of this system is that besides simply

abstracting this geometrical information from a pair of

lines, the system then tends to reify the surface suggested

by those lines. In this case the stimulus of the converging lines in

plane e will tend to propagate coplanar activation

throughout plane e, thus filling-in every point in

the surface suggested by those lines. The filled-in surface will

automatically be represented at the correct distance and orientation

relative to the egocentric point, at the center of the perceptual

sphere. Any additional visual cues which are consistent with

the perceived surface would strengthen that percept and give it a more

precise perceived form and place, while any cues which were

inconsistent with it would tend to suppress the percept of

that surface.

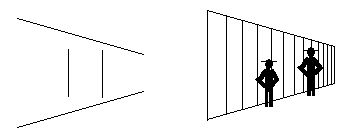

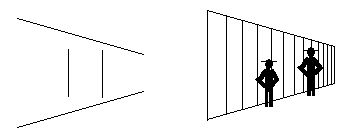

This mechanism now offers an explanation for the Ponzo illusion, where

the two vertical lines appear to have different lengths, due to the

presence of the converging lines which suggest a depth interpretation.

The Ponzo Illusion

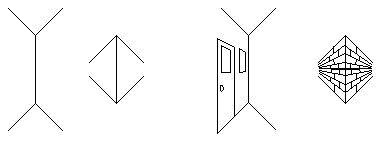

This mechanism also explains the Mueller / Lyer illusion where the

vertical lines which are of the same length appear to be of different

lengths. Again this illusion makes sense in a spatial context,

because the line which is made to appear farther in depth becomes

perceptually larger, while the one that is made to appear closer in

depth becomes smaller.

The Mueller / Lyer Illusion

Return to argument

Return to Steve Lehar