This is a summarized version of a long debate I had with Bill Adams on the epistemology of conscious experience, or the debate between Direct Perception v.s. Representationalism in September 2005.

See also the Cartoon Epistemology

SL: Introduction

BA: Very enjoyable thanks. Some missteps & false dichotomy.

SL: Care to elaborate?

BA: What is an image? What is a representation?

SL: Solid volumes with colored surfaces in a spatial void.

Bill Adams' Response to Cartoon Epistemology

BA: My reactions to Cartoon Epistemology

BA: 1: Two frames of reference & how to switch between them.

BA: 2: Pictures are mental judgments. The eye is not a camera

BA: 3: False statement: Sides of road are not straight and parallel.

BA: 4: The appearance diverges from agreed upon reality.

BA: 5: Two realities? How to switch between them?

BA: 6: Our bubbles are synchronized by mind-independent reality?

BA: 7: Mind must be non-causal or it violates conservation of energy.

BA: 8: How do you see discrepancy if you can't see the external world?

BA: 9: How can brain see itself? Capacity for self-reflection?

BA: 10: How to see the discrepancy if you can't see the external world?

BA: 11: Are there three realities? Or four?

BA: 12: The sensorimotor homunculus is not the rational self-reflective homunculus

BA: 13: What kind of "force" is "motivational force?"

BA: 14: What is the other reality? The brain or the world? Contradictions.

BA: 15: Your swipe is not fair. You defeat a straw man.

Steve Lehar's Response to Those Points

SL: 1: The promise was fulfilled!

SL: 2: A photo is an image; The eye is like a camera.

SL: 3: The phenomenal world is both straight and curved.

SL: 4: Phenomenal perspective is not social consensus.

SL: 5: We experience a warped view of an undistorted world.

SL: 6: There is an objective external world.

SL: 7: Experience is causal, not an epi-phenomenon.

SL: 8: We see the world through experience.

SL: 9: We know a dream through its inconstancy. There is no experiencer.

SL: 10: Same as point 5.

SL: 11: There are only 2 realities.

SL: 12: Body-image is not the self-reflective homunculus. There is no need for one.

SL: 13: A mental force moves mental objects.

SL: 14: There are two realities; mental experience is in the brain.

SL: 15: How have I misrepresented?

Bill Adams' Response

BA: Comments on SL's rebuttal.

BA: 1: The duality of phenomenal experience.

BA: 2: Are there images without observers?

BA: 3: On mental synchrony.

BA: 4: The causality of experience.

BA: 5: Kantian duality.

BA: 6: The inner surface of your skull.

BA: 7: Mediated v.s. direct visual experience.

BA: 8: The homunculus.

BA: 9: Representationalism, science, and materialism.

Steve Lehar's Response

SL: Comments on BA's rebuttal.

SL: 1: The duality of phenomenal experience.

SL: 2: Seeing your retinal image.

SL: 3: Images without observers.

Bill Adams' Response

BA: Comments on SL's rebuttal.

BA: Dualism

BA: Immaterialism and Spiritualism

BA: Visualizing Mental and Physical

BA: Causality

BA: Mind and the Laws of Physics

BA: Occam's Razor

BA: Conjectures and Refutations

BA: The Scope of Science

BA: Scientific Observation

BA: An Inconclusive Conclusion

Steve Lehar's Response

SL: Comments on BA's rebuttal

SL: Dualism

SL: Immaterialism and Spiritualism

SL: Visualizing Mental and Physical

SL: Causality

SL: Mind and the Laws of Physics

SL: Occam's Razor

SL: Conjectures and Refutations

SL: The Scope of Science

SL: Scientific Observation

SL: An Inconclusive Conclusion

SL: 8 Final Questions

SL: 1. Is your experience spatially structured?

SL: 2. Where is your visual experience located?

SL: 3. Is there an objective external world?

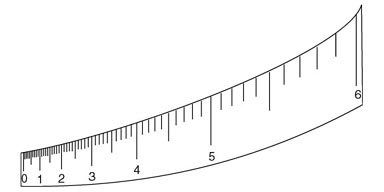

SL: 4. Do you see the warped ruler as regular and warped?

SL: 5. How would your experience differ from the diorama?

SL: 6. What would subjects say in Hallway Experiment?

SL: 7. Does mind change the state of the brain?

SL: 8. Would this be a scientific hypothesis? [invisible sphere]

Bill Adams' Response

BA: Comments on SL's rebuttal.

BA: 1. Is your experience spatially structured?

BA: 2. Where is your visual experience located?

BA: 3. Is there an objective external world?

BA: 4. Do you see the warped ruler as regular and warped?

BA: 5. How would your experience differ from the diorama?

BA: 6. What would subjects say in Hallway Experiment?

BA: 7. Does mind change the state of the brain?

BA: 8. Would this be a scientific hypothesis? [invisible sphere]

Steve Lehar's Response

SL: Comments on BA's rebuttal.

SL: 3. Is there an objective external world?

SL: 4. Do you see the warped ruler as regular and warped?

SL: 7. Does mind change the state of the brain?

SL: 8. Would this be a scientific hypothesis? [invisible sphere]

Hi Bill,

On the subject of subjectivity, and reflexive examination of experience, I thought you might enjoy this Cartoon Epistemology.

.//cartoonepist/cartoonepist.html

Steve Lehar

Thanks, Steve, very enjoyable. I could show the series to my cogsci

class.

I have defended Gibsonian direct perception in the past. I did a

post-doc with him in the late 70’s. But I drifted away from his

point of view as I discovered that it was not really a single point of

view, but a melange of many incompatible ones.

My theoretical feedback on your cartoon is that it makes a couple of

missteps that lead to a false dichotomy at the end. But it’s a

clever strategy. If you can get the reader to accept the frame of

reference, then you control the kinds of questions that can be asked.

[Note:Underline highlights key points addressed

in the response.]

Would you care to elaborate on the missteps and the false dichotomy?

Most of my anti-representationalist friends agree with most of the

responses of the little fat guy. In fact those responses are modeled

on the many debates I have had with different people over the years,

so I thought I had a pretty good handle on the arguments of the

opposition. But if I have missed something I would be interested to

know about it. As you know, nobody fits exactly into discrete

categories, and there are an infinite variety of variations.

As for alleged missteps, as you know they are in the eye of the

beholder. But I would ask you these three questions:

First, visual experience is (in my view self-evidently and

indisputably) spatially continuous and volumetric. Every point on

every visible surface is experienced simultaneously and in parallel,

and every point is perceived in a specific spatial relation to every

other point in that surface in three dimensions. And all of the points

in a surface are perceived as a spatial continuum within the surface

to a certain spatial resolution, and the surface is perceived to be

embedded in a 3-D volumetric space. In other words, visual experience

takes the form of...

In other words, visual experience is expressed in the form of an

*analogical* representation.

Lets leave point 3 until I hear your reaction to this much.

My reactions [to the Cartoon Epistemology] may be of interest to you.

Husserl identified the “natural attitude” in which the world is

accepted naively as it appears, and the “phenomenological

attitude” in which the world is not as it first seems

(“strange” as you say). To switch from the natural to the

phenomenological, one performed a mental gymnastic called the

“transcendental reduction.” You, apparently, are adept at it.

Husserl never could explain why there should be two apparently

incompatible frames of reference, nor how, exactly, one switches

between them. Your introduction seems to promise that you will

explain. In the end, that promise was not fulfilled.

[Note:Underline highlights key points addressed

in the response.]

There is a picture on the camera’s film only because some human

being says so, just as there is a face on the moon for the same

reason. Do you agree that there is no objective face on the moon? But

you seem to think that there is an objective, mind-independent picture

on the film. Why? There is no face on the moon and there is no

picture on the film.

“Pictures” are mental judgments. The pattern of silver nitrate

precipitates on the exposed film is a consequence of the refractive

properties of the camera lens. We, the visually perceiving humans,

look at the pattern and say, “It looks similar to the scene beyond,

only smaller.”

The difference between the chemicals on a film and the activity on a

retina is that nobody is looking at the retina, least of all

the owner of the retina. Nobody ever says, “It looks similar to the

scene beyond.” Not even the brain can do that.

The analogy between eye and camera is thus unsound.

But they’re not straight and parallel as far as the eye can see.

As far as the eye can see is the horizon, where the curbs converge at

a vanishing point. So the statement is patently not true. Why start

out with a false statement?

What you want to say perhaps is something like, “Despite

appearances to the contrary, we have agreed, by consensus and

intellectual tradition, that the curbs are parallel all the way to the

horizon. The appearance diverges from that agreed-upon reality.”

However, in a surprising move, you suggest instead that we take the

melon rind as the reality.

This suggestion subtly shifts the discussion from reality and its

appearance, to a scenario in which there are two realities, one a

scale model transform of the other. Some perceiving subject perceives

them both and finds a discrepancy.

That’s a huge shift in assumptions and it should have been made explicit.

You simply assume that our bubbles are “synchronized.”

There’s no way you could know that, of course.

But since you assume it, then you have to explain it, and your

preferred explanation is that the mind-independent reality beyond

perception, what Kant called the noumenal world, is causal, while the

bubble world is merely the effect of the external world.

You make an error however when you say that there must be a real house

there to be the common cause of both perspectives.

A “perspective” is a function of the perceiver’s unique

location in time and space. It is not caused by the house, but by the

perceiver.

What you should have said was that the noumenal house is the cause of

each bubble. You don’t know if the bubbles are identical. In fact

we know that they are not, since two individuals cannot occupy the

same space at the same time. They have different perspectives.

Mind would have to be a non-causal consequence of brain

activity (a byproduct), otherwise physical laws of conservation of

energy are violated. So the bubble reality, being mental, is only an

effect, not a cause. So in comparison to WHAT, would mental

experience ever be strange? It simply is what it is.

You seem to assume that the mind can magically bypass brain and have

direct access to the external world. It then compares its “direct

access” to the world with what the brain provides, and finds a

discrepancy. But that is an impossible and illogical scenario.

Well, somebody has to see the external world directly. Otherwise, how

do we know that there is a “strange” discrepancy, and how could

we hypothesize a transform function between the realities?

Your idea here is logically inconsistent (as was Kant’s idea of the

two worlds). If all you know is the bubble reality, how do you know

there is a skull beyond that reality? You can’t know what is

beyond knowledge. You can’t perceive what is beyond perception.

Furthermore, seeing the world “through private conscious

experience” of it, is problematic. The private conscious

experience IS the seeing experience.

When you use the word “through,” you imply that the subjective

locus of seeing is somehow different from the seeing experience. Like

a person going “through” a doorway, or looking “through” a

telescope. What entity is it that sees “through” private

conscious experience? Your proposal here is uninterpretable.

Hallucinations and dreams are only interesting because of the

discrepancy they present between the external and bubble realities.

But how does that discrepancy arise if the mind knows only what the

brain gives it?

Actually, in your thesis, the mind would not even know the bubble

reality. The mind IS the bubble reality. From what point of view

would the mind be able to realize that it is “IN” a bubble

reality?

Self-awareness is required in order to reflect upon the processes and

products of perception. But as an inert byproduct of brain activity,

mind would not be capable of self-reflection. It perceives, but

cannot know that it perceives. There would therefore be no bubble

reality, only “reality.”

Without a homunculus, there is no discrepancy between appearance and

reality and you have no problem to solve.

The brain only processes the activity of the receptors. It knows

nothing of “the world”. Only the mind knows the world. It’s

no good to pretend that the brain is a mental homunculus.

If you are trying to suggest that all we ever perceive, mentally, is

brain activity, then the brain IS the world, as far as perceptual

reality is concerned. But in that case, no discrepancy could ever

arise between appearance and reality.

Are you now suggesting that there are THREE realities: External

world, brain representation, and mental experience?

The phrase “internal replica” is ambiguous. Does it refer to

the brain representations, or to the bubble reality of experience?

If you seriously mean that one “sees the remote external world

THROUGH the medium” of a replica, you would have to invent a FOURTH

reality where some homunculus could sit and view the bubble reality,

and compare it to the other two realities, brain map and external

world.

If, on the other hand, you mean to say that the internal replica is

the brain representations, then the bubble reality is merely a

transform of the brain representations. Mental experience is thus of

the brain and we can forget about the so-called external world.

So, which of these two incredible hypotheses are you endorsing:

There are FOUR realities, and perception involves #4 (the homunculus)

reflecting on the others, or Visual experience is actually perception

of the brain. The world is irrelevant.

Your “perceptual homunculus” is just another brain activity.

That’s fine, although misleading to call it a homunculus. It is

more like a sensori-motor comparator. What brain scientists call the

sensory homunculus is simply a set of cortex areas mapped to

receptors. That’s not what you mean. You are talking about an

active, computational sensori-motor comparator.

But your sensorimotor homunculus it has nothing to do with the mental,

rational, self-reflective homunculus required for you to support the

hypothesis that perception involves viewing the external world *via*

the medium of the bubble world, the way a person might view the world

through rose tinted glasses.

The idea of motor representation in the brain is non-controversial,

and your presentation of it is entertaining, as is your discussion of

sensori-motor coordination. But it doesn’t have much to do with

your thesis. And it does NOT excuse you from accounting for a mental

homunculus. Sensorimotor coordination does not explain WHO sees the

world *through* visual experience.

Indeed, you introduce a second mental homunculus in the motor

discussion when you assert ‘free will’, or perhaps you mean only

to expand the powers of the original mental homunculus (which you do

not acknowledge) from evaluation of visual experience to exertion of

intentionality, or will. Either way, your sensorimotor comparator

does not meet the requirements you need to support your theory.

I will not comment on your theory of motivation until you tell me what

kind of a “force” a “motivational force” is supposed to

be.

Your thesis (as best I can understand it) is that the world we see

is the bubble world, a transform of some other reality. It is unclear

what you think the other reality is.

Sometimes you suggest it is the brain (sensori and motor

representations), and other times you suggest it is the external world

itself. Both hypotheses have internal contradictions.

If mental experience is of the brain, then the external world is

not relevant to your theory of perception (and indeed, cannot even be

known). But in that case, there is no possibility of a discrepancy

between brain operations and mental experience.

If mental experience is a picture of the external world, then you need

a mental homunculus to make the judgment that it is looking at a

picture of the external world, to compare the picture to the external

reality, and say, “This picture is similar to the scene beyond.”

The homunculus would have to magically know about the external world.

Your swipe at the theory of direct perception is not really fair,

since you only presented that point of view as a straw man.

There’s no denying that this is a creative and entertaining way to

present some important concepts in perceptual theory, Steve. Thanks

for doing it, and for making it available to me.

Best regards,

Bill Adams

Response to the many points:

That promise was very much fulfilled, and it was fulfilled with a

unique and original observation: That the phenomenal world is both

straight (Euclidean) and it is curved. The sides of the road

are perceived to be straight and parallel, and yet they are also

perceived to meet at a point, and this is explained by the fact that

our reference scale by which we judge objective size and

straightness is itself bent, or warped. The duality of experience is embodied

in the representation itself. This duality is an observed property of

the experience itself, without regard either to the geometry of the

external world, nor to the neurophysiological mechanism in the

brain. To "switch between them" you attend either to the

shape of the experience itself, which is warped and bulgy, or to the

geometry of the warped and bulgy reference grid, whose curved lines

and shrinking perspective are by definition actually straight

and parallel and equally spaced. If you ignore the curvature of the

visual world, and see the road as straight, and ignore the fact that distant

objects appear smaller, (as we commonly ignore in everyday experience)

then you are perceiving the objective component of the

experience. Both the curved and the straight geometry are observed

properties of the phenomenal world.

If you deny that you see the world as warped and bulgy, check out my Hallway

Experiment and tell me if you would answer the questions any

different than my subjects did.

An image on the photosensor array of a video camera is only a picture

to a human user of the camera, it is not a picture to a computer

that copies and processes that video data. [Paraphrased]

This concept, cleverly disguised as merely a question of definitions,

is actually the key concept behind the Gibsonian view of perception,

and it embodies the key epistemological error of that way of

thinking. This foundational assumption needs to be examined and

justified, rather than presented as a statement of indisputable fact,

because the whole question of the directness of perception (or

otherwise) hinges critically on this "definition".

In the first place the definition of what is or is not a picture is a

matter of consensus, or how people generally understand the concept,

rather than a question of dogma or logical necessity. And most people

would consider the image at the back of your retina to be a "picture",

as they would a pattern of light on the photosensor array of a video

camera, whether or not there is somebody viewing it. The whole field

of digital image processing is based on the notion that it is pictures

or images that are being processed. Image processing operations such

as image convolution are spatial computations with spatial effects on

the spatial properties of the processed image. It would be absurd to

define these as non-images unless or until a user shows up to "see"

them. Wouldn't it be more reasonable to define images as spatial

patterns in some medium contrived to represent the spatial pattern of

something else, like the brightness of light on a picture plane? This

definition would be agnostic to whether it is "viewed" by a human or a

robotic "observer", or by any observer at all.

I agree that there is no objective face in the moon. But would you

agree that there is a face in the moon to a computer image

recognition program that is tuned to detect faces? If given an image

of the moon, it will try to interpret the image in terms of its stored

prototypes or tempates. If there is enough similarity, the face

detector will trigger, and the program "sees" the face in the moon. To

the computer program, there is a face in the moon, and to the

computer programmer it is meaningful to talk of the existence of

objective "faces" in images, as defined by the probability that they

would trigger the face detector, and people can meaningfully talk of

the objective existence of faces in photographs as defined by the

probability of being recognized as faces by other people.

But why does a Gibsonian object so vehemently to what is just a

question of definitions? Why is this very notion pronounced taboo? A

"category error"? Self-evidently false? It is taboo because just

allowing that there are pictures in video cameras, immediately raises

the obvious analogy between the eye and a video camera. Both

have lenses, and adjustable apertures, light-sensitive photosensor

arrays, and wires to transmit an image to a computational

brain. How can one reasonably deny

that the eye works like a video camera in that it records an image and

transmits it to the brain?

Now it may be that the eye works by an entirely different principle,

as Gibson suggests. But until that other principle can be explicitly

described and conclusively demonstrated, (which Gibson did not provide) the

simplest, most parsimonious explanation favored by Occam's Razor, is

that the eye records an image and transmits it to the brain. And if

this first stage of sensory processing already makes use of a

representation, representing a pattern of light with a pattern

of electrochemical activation, then representationalism is at least

workable in principle. In fact the principles of representationalism

have been demonstrated in actual robot models equipped with video

cameras that transmit images to a computer brain for processing.

Gibson's

dogmatic denial of the existence of images in the brain or even on

the retina, all stem from his foundational epistemological assumption

that the spatial structures that we see in our experience are the

spatial structures of the world itself. That there is no

representational entity, the sense data, that stand as

intermediaries between the world and our experience of it. But this

hypothesis must be proven against the more obvious representational

alternative. One cannot simply begin with the assumption that

perception is direct, as an axiomatic fact. This is supposed to be

Science, not dogma. That initial assumption needs to be

justified against the representationalist alternative. And it needs

to explain how perception can be direct when the experience is a

dream, or hallucination, which are definitely "image-like" spatially

structured experiences. Where are those hallucinated images if not in

the brain? How can we experience a spatial structure that does not

exist in the material universe known to science? Is the brain not just

a computational machine?

There is a duality in phenomenal perspective; it is experienced to be

curved like a fish-eye-lens view, with distant objects appearing

smaller, and yet we also perceive the world as undistorted, with

distant objects undiminished in perceived objective size. In everyday

naive perception (natural attitude) the curvature is invisible to us,

we would swear that the sides of the road are straight and parallel

along its entire perceived length, and we can easily tell when the

road actually narrows, as opposed to narrowing due to perspective. In

naive perception the sides of the road are perceived to be

straight and parallel and equidistant, even as they clearly converge

to a point! This may not be true of a two-dimensional

photograph of a perspective scene, but it is certainly true of

a real road viewed in the world.

This statement is not false!

No! That suggests it is some cognitive reasoning process or social

consensus. But the ability to compensate for perspective is far more

pre-attentive and beyond cognitive influence, a more primal and

hard-wired primitive function. No-one could convince you to perceive

the road as converging when you can see that it isn't, or

vice-versa. And yet that judgment is easily fooled by contrivances

like the

Ames' Room, and by perspective

dioramas that engage and deceive that same automatic perspective interpretation mechanism.

Perceptual constancy has been confirmed even in simpler animals. For

example newly hatched chicks who, when trained to peck at the larger

target, even pick correctly when the larger target appears smaller by

perspective. This is a very low-level hard-wired function that must be

common to virtually all visual animals.

I am NOT taking the "melon rind" as "the reality", I am merely

pointing out the observed properties of experience. If you

contest my observation, then please tell me what it is that you

observe. Because what I observe is two sides of the road which

I could swear appear straight and parallel as far as the eye can see,

and yet I also see those two sides meet at a point up ahead and back

behind. They do not appear to be curved like a melon slice, but they

appear straight and parallel along their entire visible length, and

yet paradoxically, they also meet at two points which are well short

of infinity, as if they were curved like a melon slice.

We do not perceive both realities and then notice a discrepancy

between them. Instead, we experience a warped and distorted world,

which we automatically and pre-attentively assume to be a warped view

of a straight world. That "assumption" is embodied literally in the

bulgy reference grid that we automatically perceive invisibly

superimposed on the warped and bulgy experience.

The principle behind this perception can be seen even when

looking at a distorted picture like this one:

Anyone looking at this picture would immediately see that it depicts a

distorted fish-eye lens view of an undistorted world. You can see that

the road is "supposed to" be straight, and that the two houses are

"supposed to" be the same size and shape, even though your direct

experience is of a curved world with distorted houses. Your perceptual

apparatus automatically and pre-attentively interprets the curved and

bulgy world as a warped view of a straight Euclidean world, even

though it has to tolerate a gross violation of Euclidean geometry in

doing so, and allow that parallel lines meet at two opposed points at

a distance well short of infinity.

In the picture the curvature is perfectly apparent, whereas when

standing on a real road, the curvature is virtually invisible, only

the gross violation of Euclidean geometry remains apparent. But the

principle by which you see a straight Euclidean world "through"

a distorted fish-eye lens world in this picture, is the same principle

by which we see the Euclidean geometry of the perceived world through

our warped experience of it.

Yes, I assume different people's experience is automatically

"synchronized" by a common objective external world. That is a core

assumption of science itself. Science assumes the existence of

an objective world, and studying that world is the objective of

science. To propose that our individual experiences are not

coupled veers towards solipsism, which I take to be

self-evidently false. Surely you don't subscribe to Husserl's extreme

phenomenological view that there is no objective reality, all that

exists is our experiences. Do you?

I don't follow your point on the causality

issue. The shape of the experience is a function both of the objective

shape of the house, and of the location of the perceiver. But I

do assume that there is an undistorted Euclidean house out

there that is the cause of the shape of my distorted experience of

it. Is that an error?

I don't subscribe to the notion that experience is non-causal,

that consciousness is an epi-phenomenon with no functional

value. For something as majestically intricate and elaborately

articulated as our conscious experience, to have evolved to such a

high level of sophistication while serving no functional role, seems

vanishingly unlikely in a Darwinean context.

Furthermore, the causality of experience is demonstrated by the fact

that a purely mental thought, such as "I raise my arm" can be made to

have direct causal consequences in the actual movement of my arm. This

is not a violation of the conservation of energy. It merely

states that mind is not some etherial non-physical entity somehow

magically superimposed on the physical brain, but rather, that mind is

itself a pattern of physical energy causally present in the physical

brain, and that is why mind can have direct causal consquences both

directly on the state of the brain, and indirectly on the state of the

body through motor action. This is the basis of identity

theory, that mind is identically equal to certain processes in the

physical brain, rather than an epi-phenomenal byproduct of the brain

with no functional value or causal potency. Although identity theory

cannot be proven to be true, neither can it be shown to be false, as

is commonly but mistakenly assumed. And identity theory provides the

most parsimonious explanation for the existence of consciousness in a

Darwinean world.

The Bubble Reality is therefore both mental and physical. Its mental

component is seen in the patterns that it exhibits in experience, and

its physical component is the physical substance of which experiences

are expressed or represented in the brain.

The mind does not "magically bypass" the brain and does not have

direct access to the physical world, but rather it attains its

information about the world indirectly, through sensory detection and

internal representations, and it plies its causal influence indirectly

through internal motor representations and motor commands.

The discrepancy detected by the mind is not a discrepancy between the

world and its representation, but rather a discrepancy between the

world of experience and our expectations of that experience. We

do not expect physical objects to morph elastically as we view them

from different aspects, our mind finds it more parsimonious to assume

that the morphing experience is a perspective transformation of an

object with fixed size and shape, and it is that fixed or invariant

configuration that we experience in naive perception (natural

attitude) despite the morphing of the actual experience.

As explained above, the discrepancy is not

between the world and its representation, but between the warped

experience and our expectations of an invariant, un-warped

objective world.

This idea is not logically inconsistent, nor is it at variance

with Kant's nouminal and phenomenal worlds. Kant declared that the

only way we can perceive the nouminal world is by its effects in the

phenomenal world. Wherever we see irregularities and inconsistencies

in the phenomenal world, objects zooming unaccountably through different

sizes, objects morphing elastically through different shapes, parallel lines

meeting at two points short of infinity, we try to account for them as

perspective transformations on rigid objects, because that is the most

parsimonious interpretation of our experience.

We do not see the objective world and its properties directly, but

rather we infer its properties from the world of experience

that we do see, by way of the warped reference grid.

As for your complaint about the wording: "seeing the world 'through'

private conscious experience of it." This is not problematic if you

understand that "through" is being used in the sense of "by way of",

the same way that we see the remote world "through" our television set

by way of the medium of glowing phosphors on a glass screen, that

gives us the illusion of seeing the world literally "through"

the television as if through an open window.

As with the television analogy, the subjective locus of seeing is in

the representation, i.e. in the glowing phosphors on a glass screen,

even though the pattern apparent on that screen represents a remote

external scene. According to representationalism, it is possible to

"see" something remote by way of the representational medium in your

brain, without ever actually "seeing" anything beyond your brain.

I understand that your objection to this terminology is rooted in your

objection to the whole notion of sense data as intermediaries in the

act of seeing, which you consider to be impossible in

principle. Although I don't aspire to convince you otherwise, I hope

you will at least concede that the representationalist view of

perception is at least equally plausible as the direct

perception view, and that it is not dogged by insoluable

paradox as is often assumed, or at least no more than the alternative

direct perception view, a view that is in fact dogged by the

insoluable paradox of how something can be experienced that is not

explicitly represented in your brain.

The only way the mind can notice a case of dream or hallucination is

by the inconsistency and inconstancy of the dream or hallucination,

where unlike in waking experience, people and objects can morph

unaccountably into different things, and the plot, or story line of

your experience often takes abrupt and illogical turns.

The way we know of the objective properties of perceived objects is by

their observed constancies. Objects have existential permanence, they

don't tend to appear or disappear unaccountably, as illusory objects

often do. We can usually find them where we last left them unless

somebody else moved them in between. Objects morph by perspective, but return to

the same shape when viewed from the same perspective, as if they had

an objective unchanging shape underneath their changing

appearance. Other people report seeing the same objects we can see,

and the same places in the world, as if we were all living in the same

world that continues to exist even in our absence. We can never be

absolutely certain of the existence of that objective world, because

we can never see it directly. But we can be pretty sure of the

objective existence of the people and objects in our everyday world,

or at least, about as certain as it is possible to be certain of

anything.

How does the mind experience itself in the absence of an "experiencer"

there to experience the experience? This is the old homunculus

objection.

The straight answer is that we don't know how the brain can

experience its own spatial structure, or why it should produce certain

patterns of experience in the process of perceptual computation. We do

however know for a fact that we have experience, that experience exists,

and it exists in the form of a vivid spatial structure, like the

experience of the world you see around you, the one that disappears

whenever you close your eyes. Wherever it is located, and of whatever

it is composed, that experience exists, and it exists in the form of a

volumetric colored structure that comes into existence only when my

brain is engaged in perception. The only question is where is that

structure, and of what is it composed?

Gibson's explanation is that the experience is located out in the

world, on external objects themselves. But he does not explain how

that experience comes to appear on external objects when it is a

product of the brain, nor does he explain what that experience is

composed of, or by what mechanism it is constructed by the brain, or

how it can hold spatial information in the absence of a spatial

representation. So the problem of experience is at least as

mysterious in the Gibsonian view as in the representationalist view.

In fact it is far more mysterious and paradoxical than the

representationalist view. Because according to representationalism,

the patterns of our experience are physically located as patterns of

energy in our physical brain, causally coupled to sensory input and

motor output through nervous pathways. In the Gibsonian view

experience is located out in the world, but is a consequence of

processes in the brain. There is a vital causal link that is missing

in that explanation, the causal link between the brain and the spatial

experience that it projects into the world. The experience, as a

spatial structure, is undetectable by scientific means in the space

where it supposedly exists. It is a structure that is experienced,

but does not exist. Surely it is more parsimonious to assume that

experience is a structure in the brain, constructed in the service of

perceptual computation.

Representationalism begins with the confident assumption that

conscious experience will eventually succumb to a physical, scientific

explanation, as a physical process in the physical brain. The brain is

a computational device that operates on physical principles, so it

must be possible in principle to build a machine that has experience

by the same basic principle. Let us set out to discover the brain

mechanism behind the phenomenon of visuospatial experience, and how it

paints the pictures of our experience, rather than to deny that our

experience is spatially structured, and give up the search before it

has hardly started.

No there are not three realities, nor four (!) only

two, the nouminal world and the phenomenal world. But the

phenomenal world has two manifestations, objective and

subjective. Subjectively the phenomenal world is the spatially

extended volumetric world of our experience. Objectively, the

phenomenal world is a representation in our brain: That is, it is an

actual physical substance or field of energy that is experienced as a

spatial structure whenever it comes into existence, and vanishes into

non-experience when the field breaks down, like the image on a

television screen when the power is turned off.

This is the aspect of representationalism that is the hardest to

swallow. How can a field of energy in your brain become conscious of

its own existence and spatial structure? I admit from the outset that

this seems at first sight to be frankly incredible.

But what is incredible is that we do have experience, and yet we know

for a fact that experience exists. And as a materialist, I would like

to believe that experience must have a physical basis in the brain.

But the Gibsonian "direct perception" view does not escape this

same paradox! If perception were direct, it would

still be a mystery how we come to experience the world. In

fact, in the Gibsonian world view this paradox only deepens

because now we are expected to believe that we can become magically

aware of objects and surfaces outside of our body, out in the

world itself, where there is no computational or representational

hardware available.

It is more parsimonious, and less deeply mysterious, to claim that we

can become aware of patterns of energy in our brain, than of patterns

out in the world beyond our brain.

Quite correct. The body-image homunculus is not the self-reflective

homunculus that "sees" the world of the internal theatre. That body is

a perceived object, composed of the same "substance" as the rest of

the experienced scene, because the picture of the world would be

incomplete without a picture of one's own body in the world.

According to representationalism, you do not need a viewer to view the

internal scene. Patterns of energy in the brain correspond directly to

patterns of shape and color in our experience, just as the pixels in

an image data array correspond directly to pixel brighnesses in an

image.

We do not see the blue sky out there from in here behind our

eyeballs, but rather, we experience the blue sky to exist out there at

the location it is perceived to occupy. If my body-image homunculus

were to disappear, I would have a disembodied experience, like an

invisible ghost, but my experience of the blue sky out there would

continue in the absence of any kind of viewer at the egocentric point.

In physics a force is something that can set objects into motion. In

the mind a force is something that can set mental objects into

motion. The body image homunculus is drawn by a mental force of

attraction that moves it towards attractive stimuli.

But since the body-image homunculus is coupled to the posture of the

external nouminal body, the causal force of mental motivation has its

effects both on the internal model of the body directly, and on the

external physical body indirectly where it is expressed as an actual

physical force that pulls it in the direction of the attractive force

in the mental representation.

Causality can only be transmitted from

mind to brain if mind is a physically measurable entity with an actual

presence in the world known to science.

There are two realities: The physical world known to science, composed

of matter and energy in space, and the phenomenal world that consists

of volumetric colored spatial patterns of experience in phenomenal

space. If mind is to ever succumb to a rational, materialistic

explanation, then the patterns of mind must necessarily correspond to

patterns in some physically measurable medium in the brain. Mind and

brain are not separate, one being physical while the other is pure

experience, but rather mind is a physical pattern explicitly present

in the brain.

Mental experience is in the brain, but the external world is

still relevant, and can be known indirectly through those

representations, because the representations take on the shape of the

external objects they represent, and thus we can see the shapes of the

external world through the medium of their perceptual effigies. There

can indeed be no discrepancy between brain operations and the

corresponding mental experience. But there can be plenty of

discrepancy between mental experiences and the world that those

experiences attempt to represent, especially in the case of dreams and

hallucinations.

Mental experience is indeed a picture of the external world, but you don't need a homunculus to make a judgment that it is looking at the world.

Well please enlighten me as to where I have misrepresented direct

perception, so that I can represent it more fairly.

Thanks very much for your feedback. Hope to hear more from you!

Steve Lehar

Hi Steve,

Thanks for formatting our conversation into HTML, and I presume,

posting it. I think the dialog is stimulating and potentially useful

to others.

I have a few comments on your rebuttals. I will avoid going over old

ground and focus only on the most important points we have disagreed

on, in the interests of mutual understanding.

You say the phenomenal experience is straight (Euclidean) and curved.

I cannot experience both aspects simultaneously. At best it is like

the oscillation of Necker cube aspects. The switching time between the

two modes seems quite fast, but not zero. If you say you can

experience both aspects at once, then our perceptual experience

differs fundamentally.

Your explanation of this duality is, for me, perplexing. If the

reference scale by which we judge objective size and straightness is a

bubble, then how would it be possible to ever experience the bubble

itself? No matter what you looked at, you would get Euclidean

geometry.

One answer might be that you mentally discard the reference scale in

order to experience the bubble world. But if use or non-use of the

reference scale is optional, and apparently under conscious cognitive

control, then all you have done is reassert my proposition that there

are two alternating attitudes for apprehending phenomenal experience.

And we still lack an explanation of how or why, one switches between

modes.

Saying that the duality is an observed property of the experience

itself is misleading. It is a subjective rather than an objective

property of the experience. I think it is an error of reification to

objectify it.

My interpretation of the duality as bimodal is consistent with the

results of your hallway experiment, and, I suggest, more consistent

with the actual questions and answers of the experimental protocol

than the idea that the experience itself is some kind of a hybrid

unity. (Ingenious experiment though!)

This is a fundamental point of difference. Forgive me if my point of

view sounds dogmatic, but I have a hard time seeing any reasonable

alternative.

The image on the back of the retina is a picture, I admit. Image and

picture are almost synonymous terms. I am not trying to split that

hair.

When a doctor looks into your eye, she might see your retinal image.

That’s fine. An image is an interpreted optical pattern. As long

as there is an observer to interpret, there can be an image. So I

accept the common sense view that the retinal image is an image.

However, we know that a person never sees their own retinal image. So

if we are talking about phenomenal experience, that is, first person

experience “from the inside” as it were, how the world appears

to one, it is quite clear that there is no retinal image. That is the

basis on which I say that there is no retinal image involved in the

experience of perception.

What about images in the third-person, scientific, observational

context? Even here, I do not agree that there are any objective

images. You give the example of a computer image recognition device

that is tuned to detect faces, and when pointed at a face or a picture

of a face, gives some appropriate output. This is supposed to

demonstrate the objectivity of images.

The example embodies a common error afflicting AI advocates. I

suffered under it for decades. A computer program or engineered

device is an implementation of the programmer or designer’s

assumptions, values, and rules for pattern recognition. The device

does not literally detect images. Its designer or programmer does, in

deferred execution, through the medium of the device.

When a novel is sitting on your bookshelf, do you think that the

characters are writhing about in the pages all day and all night? Of

course not. The drama represented in the novel is the author’s

story, communicated in an asynchronous mode. The author uses a medium

of deferred message delivery. The author might even be dead by the

time the reader receives the message. But at no time do we believe

that the book itself understands the drama written on its pages.

The analogy holds for the computer program. The programmer tells us

what he or she believes are good rules for pattern recognition.

Strong light usually comes from above. A size gradient indicates

depth of field. Properties of the optic array are such and such.

That’s fine. I admit that the programmer is a human being and can

recognize patterns according to certain rules and interpret some

patterns as representational images.

Writing out the rules for image identification and interpretation, and

storing those rules in a medium for later execution, does not confer

image-recognition powers to the storage device. To believe that it

does is an incredibly naive error to me (Although, as I say, I once

labored under that error. Today, I don’t see how I could have).

You say that objective faces in images can be defined by the

probability that they would trigger the face detector in a device. I

agree that people can meaningfully talk of the objective existence of

faces in photographs using that operational definition. It is

meaningful only in a sort of shop jargon however.

If the face detector is in a spacecraft like Voyager I, traveling

through interstellar space away from Earth, processing pictures

provided for it, and nobody will ever inspect its activity or output,

would you still say it is detecting faces? You might say so, and I

would say, “How do you know?”

You would show me copies of the pictures, which I would look at and

interpret as faces, and say, yes, those are faces.

And you would refer me to the text of the computer program or the

device specifications and I would agree, yes, those describe rules

that I could use to identify faces.

You and I can identify faces and we can even specify some of the rules

we use to do so. But the criterion of a face is still a mental

judgment. It is an error of reification to objectify that judgment,

and a non sequitur to point out that an engineered device can be made

to store a description of the judgment.

I think the reification error is prevalent because of the newness of

computers and robots in human experience. When television first came

out, people would try to peer down the edge of the screen to see what

the newscaster was reading. When the movies came out it was

literally, the magic lantern. We have not yet, as a culture, fully

absorbed information technology so we tend to misinterpret it.

Are there pictures in video cameras? Only in the trivial sense that a

video camera is a device designed expressly to implement certain

pattern recognition principles that capture and later present patterns

that look like images to a person. There are many other patterns it

could capture that we would not recognize as images, but who would buy

a camera that did that? I could say that a video camera contains

potential images, because its designed purpose is to isolate patterns

that a human readily interprets as images.

I do admit that an analogy can be drawn between eye and video

camera. As you say, both have lenses, and adjustable apertures,

light-sensitive photosensor arrays, and wires. But I believe the

analogy quickly becomes misleading rather than helpful.

For example, you say both have wires to transmit an image to a

computational brain. But here is where the analogy becomes invalid.

The wires transmit only signals, not images. Why? Because there is

no image until some human (or other visual observer) says there is.

If no biological visual systems had evolved, do you think there still

would be images in the world? Would a pond form an image of the

clouds above, according to you?

It is no good to say there is an image if there is a point to point

correspondence between A and B, since some visual observer must

identify that correspondence for it to exist.

I believe that Occam’s razor favors the more simple explanation,

that images are a mental judgment, not an objective fact.

I don’t defend the Gibsonian view that locates images in the world.

I locate images in the mind, as mental judgments, or interpretations

of sense data. I am the umpire who says, “It is neither a ball nor

a strike until I call it.”

The history of psychophysics demonstrated that for simple sensory

judgments, humans are remarkably consistent among each other and

within themselves over time. On that basis, we accept that we have

“the same” or within boundary conditions, very similar sensory

experience.

That agreement does not generalize well however, as the

Introspectionist school quickly discovered. For all but the most

simple sensory judgments, there is virtually no consensus on how to

describe a particular mental phenomenon.

I think the facts favor the hypothesis that our mental experiences are

not well coupled, and that we must continually negotiate an acceptable

shared reality. (As we are trying to do here).

In the context of your theory of perception, I accept the assumed

“synchrony” of simple sensory information, but reject the

synchrony of its interpretation as Euclidean or bubble-shaped. I

think our debate here illustrates that point.

I mis-attributed your position, apparently, when I called you an

epiphenomenalist. Sorry. I understand your endorsement of identity

theory, that mind is identically equal to certain processes in the

physical brain, electrical and biochemical processes, presumably.

However, I’m afraid I find that position incoherent. If I make two

lists, one listing the qualities of mental experience, and one listing

the features of the brain, there is virtually no overlap in the lists.

Ideas have no mass or volume. They do not absorb, emit, or transmit

heat, light, electricity, radiation, or any other kind of energy.

Call me dense, but I don’t see how anyone could seriously say that

mental events are physical. It distorts the way language is used.

Furthermore, there is a logical problem. If we grant that mind and

brain are identical, then you have no problem to discuss. Your only

task is the scientific description of the brain. In that case, what

is your cartoon epistemology about?

I realize that identity theory is a well-worn argument and there is no

point in us rehashing the whole history of that debate. I should say

though, honestly, and not as any sort of put-down, that it is my

impression that identity theory has become, if not discredited, then

at least out of favor in contemporary philosophy of mind.

In contrast, epiphenomenalism is a simple thesis: mind is a noncausal

byproduct of brain activity, occurring by mechanisms unknown. That

position conserves the laws of physics and allows the existence of the

mind, but explains nothing.

Every such solution to the mind-brain problem that I have ever

encountered, and there are a lot of them, has one or more fatal flaws.

There is no solution. I myself am a dualist, an interactionist. I

say mind and body are different realities that interact. Each has

causal efficacy. That seems most consistent with common sense

experience. How they interact is a puzzle I am still working out.

I think it is possible that we agree on an important point here. You

say that the discrepancy detected by the mind is not a discrepancy

between the world and its representation, but rather a discrepancy

between the world of experience and our expectations of that

experience. I think that is correct.

Expectations might arise from familiarity, consistency, subjective

probability.

But where we differ is in deciding what is the best inference to draw

from those expectations and their occasional violations.

You say it is more parsimonious to assume that morphing experience is

a perspective transformation of an object with fixed size and shape,

and it is that fixed or invariant configuration that we experience in

naive perception (natural attitude) despite the morphing of the actual

experience.

That is the standard scientific inference. But I don’t think it is

parsimonious, for it leaves unexplained precisely the problem that

interests us most, namely, what is the nature of the transformation?

Objects that recede appear smaller, but they’re not really

smaller. The disjunction between appearance and reality is exactly the

problem to be solved.

I think you have made an honorable confrontation with that problem

with your idea of the spherical frame of reference, but as these

comments indicate, for various reasons I am not satisfied with that

explanation.

You clarify your position when you say that we do not see the

objective world and its properties directly, but rather we infer its

properties from the world of experience that we do see, by way of the

warped reference grid.

I can accept that, and the implication that perceptual “error”

is simply what we call deviations from long term expectations about

phenomenal experience.

However, it is difficult for me to see how you get from those starting

assumptions to the conclusion that visual experience is surrounded by

a skull, except by the unconvincing equation, which I do not accept,

that visual experience is identical with the brain. With that

formula, all you are saying is that the brain rests within a skull.

It’s not clear why any inference is necessary for you. The brain

is its own experience. What more beyond that does it need?

I understand and appreciate your analogy between vision and CCTV. You

want to say that the (metaphorical) phosphors of the brain are the

consequence of a long causal chain of events that began with an energy

event in the world.

You emphasize in your discussion the relationship between the ultimate

phosphors (the representation) and the causally remote world event. I

have no problem with long chains of causality and I understand how a

television image gets on my screen and in what sense it represents a

remote event.

But making that technology analogous to vision results in a confusion

of first and third person points of view. From the first person point

of view, visual experience does not have the quality of being a

consequence of a long causal chain. On the contrary, it has the

quality of being direct, that is, unmediated by a causal chain.

From the third person (e.g., engineering) point of view, you infer

that if visual experience is caused by the brain, and brain activity

is mediated by a long causal chain, then first-person visual

experience must also be so mediated. I think that is an error of

reasoning.

However, I can see where you would not agree, since if visual

experience is the same thing as brain activity, then by definition,

visual experience is mediated.

However, for we dualists, visual experience is not identical with

brain activity, so we can say without contradiction that visual

experience is unmediated, or direct.

Visual experience can be intellectually analyzed into phenomenal sense

data components, such as the Gibsonian invariants, but that is a

different exercise than the direct visual experience itself, which is

Gestalty. Both Gibsons were adamantly anti-associationist, and they

converted me to that view.

However, I do not agree with the Gibsonian idea that visual experience

is direct because the Gestalt patterns are objectively in the world

and “picked up” by osmosis, or whatever. When Gibson got to the

end of his explanatory rope he resorted to the mysterious metaphor of

“resonance” between the experience and the world.

But at least he never made the “error” (as he and I would both

call it) of identifying experience with the brain. His gift was

intuitive phenomenology of visual experience. He knew perfectly well

that the brain has no phenomenology, and in keeping first and third

person points of view distinct, he saw no reason to discuss

third-person phenomena such as brain representations, retinal images,

and so on.

He did, alas, finally confuse first and third person points of view in

his later theory of affordances. His masterwork, in my opinion, was

the 1966 book, The Senses Considered As Perceptual Systems, in which

he did the visual phenomenology without resorting to associationism or

representationalism.

We’ve already been over this, so I’ll be brief. You say that

according to representationalism, you do not need a viewer to view the

internal representation. Patterns of energy in the brain correspond

directly to patterns of shape and color in our experience.

In fact, you should say that patterns of energy in the brain are

patterns of experience. The identity theory has no need of a concept

of correspondence.

My objection is that it does not seem to me that my experience is a

brain. It just doesn’t have any of the qualities of a brain.

You say that mental experience is indeed a picture of the external

world, but you don't need a homunculus to make a judgment that it is

looking at the world.

I understand that for you, “looking” simply is brain activity,

so you can say that no homunculus is needed to look.

But in that case, why not just define brain firings in area 17 as

“looking?” What’s the point of having the picture at all?

I don’t think it is true that representationalism entails

materialism. I can be a non-materialist (e.g., a phenomenologist) and

appreciate that one pattern of experience represents another. Indeed

that is the basis of language.

Science though, necessarily entails materialism, since it depends on

measurement, and only physical things can be measured. In my

dualistic world view, therefore, there cannot be a science of mind,

since the mind is immaterial.

Since I find identity theory incomprehensible, I have no interest in

trying to equate the principles of mind to physical principles.

Rather, I think it will be more productive in the long run to find

ways to adjust the basic principles of science so that it can support

an inquiry into the mind. Some steps in that direction are being

taken by some cognitive psychologists.

I can’t understand why materialists would enjoy reducing their

mentality to atoms and molecules, which have no inherent meaning. What

is human life without meaning?

Not only is material reductionism self-destructive, but success of the

project would negate the possibility of its ever having existed. So it

is paradoxically self-contradictory besides.

I think it makes eminently more sense to accept experience as it

appears, which is directly in the mind, with little evidence of

biological mediation. That’s an empirical starting point, rather

than a doctrine. Figuring out how to connect experience with

biological embodiment is an important question, but unfortunately, one

that is not at the present time susceptible to scientific method.

Best regards,

Bill Adams

Hi Bill,

Thank you once again for your very thoughtful reply. It is a genuine

pleasure to be debating someone who is clear-thinking and without a

hint of defensiveness or insecurity, just an honest seeker after

the truth, even if you are profoundly misguided.

In order to avoid an exponential expansion of our debate into

innumerable parallel threads, I have confined my responses to a few

key central points. I think we are honing in on the central

differences between our viewpoints, even if we are no closer to coming

to any agreement.

Steve

You say in message 8 point 1

Forget about phenomenal perspective, and just take a look at this

warped ruler. (Intended as a 2-D image, not a perspective sketch)

Do you not see both a regular scale, and a distortion applied to it?

Do you not see both the scale and the distortion simultaneously? There

is no Necker-cube instability here, there is just one experience, it

is of a warped scale, and that warped scale appears as a

regular scale under distortion. Perhaps a more primitive creature

would see the lines but never recognize any kind of regularity in

them. They would see only the curved lines and unequal spacing that

are literally present in the stimulus. But to humans, the regularity

appears immediately and pre-attentively as a regularity perceived

in the irregular pattern, just as you can see the cylindrical

shape of a rope even when it is coiled up. As in phenomenal

perspective, one is inclined to say "That is a ruler, and it is

bent!".

When one is in the "natural attitude" one tends to ignore the warping

of perspective, in the same way that you would ignore the warping of

this ruler if you saw it like this through a fish-eye lens where

everything else is similarly warped. You could even use the warped

ruler to measure distances in the warped world through the fish-eye

lens by simply ignoring the warp. But even when you are ignoring it,

you still see the ruler warped, it never becomes straight, even when

we "know" it to be so. Instead, it is our definition of straightness

that warps to match the warped ruler, although it does not un-warp the

ruler by doing so. This is my most profound and significant

observation on phenomenal perspective, that the experience is both

warped and straight, simultaneously. Can you reasonably deny that?

What would you predict if the subjects in the Hallway Experiment were

asked "Do you see the sides of the hallway converging, and parallel,

both at the same time, or do you see only one at a time, alternating in

succession?"

You say in message 8 point 1

It is true you never see your retinal image at the location where you

presume your retina to be located, at the back of your eye. All you

see there is an imageless void, a "window" out of which we seem to be

peering.

But we clearly do see our retinal after-images after

looking at a bright light or camera flash. And when we see them, they

appear not at the back of the eyeball, but out in the world! And in

the world they take the form of an explicit spatially-extended colored

image! Surely this is a direct experience "from the inside" of the

photochemical state of our physical retina. Is it not?

(See my Introspective

Retrogression for an exercise in phenomenology.)

This raises anew a question I asked in an earlier round for which I

have not yet received a response from you.

Is your visual experience spatially structured?

For clarity, I am talking about that component of your experience that

disappears when you close your eyes, that is, distinct from the world

which it is an experience of. I understand that it is an

experience of a spatially structured world. But my question is

a phenomenological one about the experience itself. Is your visual

experience spatially structured?

Here we get to what is really the most central point of our

disagreement, the paradigmatic difference in our views of

perception. This is probably where we will have to agree to disagree.

You state with supreme confidence that a computer program or

engineered device does not literally detect images. Its designer or

programmer does, but not the device. Are you saying here that

no man-made device could ever "see" of its own accord?

Are you hereby stating that vision is a magical mystical process that

cannot ever be reduced to an artificial computational mechanism?

In your point 9 you make the shocking

statement that:

Is this really your view??? So mind is like the immortal soul, in a

separate plane of existence where it is undetectable by scientific

means? You don't believe that there is a physical substrate behind

experience? The brain is not just a physical computational

mechanism?

But then it is your theory that violates the conservation of

energy. Because minds have only ever been observed arising out of the

operation of brains, and brains are composed of physical substance and

they follow physical laws, and mental operations consume energy that

is provided by the brain. Mind is not causally isolated from the

physical brain, the content of mind can be profoundly influenced by

the physical state of the brain, and conversely, the mind can have

causal consequences in the physical world through motor action. If

mind were really causally isolated from the brain, as you suggest,

then it could not possibly serve any adaptive function, being

effectively isolated in a separate universe, and thus it would never

have had any reason to evolve, so its existence in a Darwinean world

would be as profoundly mysterious as its principle of operation and

plane of existence.

The chief objection to your kind of dualism is Occam's razor: it is

more parsimonious to posit a single universe with one set of physical

laws, rather than two radically dissimilar parallel universes composed

of dissimilar substance and following dissimilar laws, making tenuous

contact with each other nowhere else but within a living conscious

brain. But if mind and matter come into causal contact, as they

clearly do in both sensory and motor function, in which both

information and energy are exchanged, then surely they must be

different parts of one and the same physical universe.

But there is another, still more serious objection to your

dualism than the issue of parsimony. Since the experiential, or

mind component of the theory is in principle inaccessible to

science, that portion of the theory can be neither confirmed nor

refuted. This places the mental component of your theory of vision

beyond the bounds of science, and firmly in the realm of religious

belief.

Every aspect of this world which initially seemed deeply mysterious to

our ancestors, from the motions of the planets, to the shining of the

sun, the blowing of wind, and the curse of disease, has succumbed to a

materialistic physical explanation. Even life itself, which was

considered by the vitalists of the last century to be a deeply

mysterious and fundamentally mystical phenomenon, has succumbed to an

explanation in terms of molecules and chemistry. If even life itself

can be explained in purely materialistic terms, surely consciousness

must also eventually succumb to a scientific explanation.

And even if it turns out ultimately that mind cannot be

explained by science, why would we give up the attempt before we have

exhausted the materialist possibilities? If, like the vitalists, we

declare from the outset that experience is a deep dark mystery that

can never be explained in principle, that conclusion would turn into a

self-fulfilling prophecy, and we would never come to understand visual

experience. Thank God the materialists of the last century were not

persuaded by the vitalists into giving up the search for the principle

of life before it had even gotten started!

And how can you say that mind cannot be studied by science when I have

shown quite clearly how it can? Science begins by observation, even

before it has any explanation, and conscious experience is clearly

observable, and that observation can be quantified, as I have

shown. Visual experience is a spatial structure with a certain finite

resolution that is lawfully related to the visual stimulus, with a

specific information content, and with a peculiar geometry unlike

anything in the external world. Even if mind were a mysterious

mystical non-physical entity, it would still be a spatial structure

with the properties we observe it to have, and thus it would be open

to scientific scrutiny.

In conclusion: I admit that representationalism is frankly incredible,

and thus I sympathize with your urgent effort to find a more

reasonable explanation. But as incredible as it may be, it is not

nearly as incredible as the notion of experience as a

mysterious non-physical entity that is undetectable in principle by

scientific means, and yet that somehow comes into existence from the

activation of living brains, while remaining causally disconnected

from those brains. It has spatial extendedness, but not in the space

known to science, but in some other parallel universe or orthogonal

dimension that has no causal connection to the universe known to

science, and yet physical light can make an impression on the mind

through sensory processing in the brain, and volitional thoughts can

have causal consequences in the physical world through motor action,

all without any exchange of energy or information between mind and

brain.

In the end, the real difference between us is that I am committed

almost "religiously", to a materialist explanation of mind: I firmly

believe that science will ultimately triumph over the problem of mind,

as it has already triumphed over mysteries which were at least equally

deep. The theory of direct perception, on the other hand, is an

elaborate rationalization to justify our naive realist intuition that

the world of experience is the world itself, seen directly out where

it lies beyond the sensory surface. Unfortunately it comes at the cost

of abandoning science itself, and introducing magical mystical

entities that are beyond the world known to science.

That is a trade-off that I am not willing to make.

Steve

Hi Steve,

I think our discussion does get at some very fundamental issues and I

am pleased you are posting it. I shall do the same.

However, I really must address some egregious misunderstandings in

your last response.

I don't mind letting you have the last word, since you stimulated the

discussion with your excellent Cartoon Epistemology. Feel free to

edit, or omit entirely, my comments below from your post of the

debate.

I am surprised that you do not comprehend dualism. On the other hand,

I find identity theory incoherent, so maybe I shouldn't be so

surprised. Replying may be like attempting inter-species

communication, but it has to be tried.

My dualistic position is, as I said, that mind is immaterial.

Thoughts and ideas, plans and memories, take up no space, have no

mass, do not emit, transmit or absorb energy. Immaterial means

non-physical, intangible, and consequently, not susceptible to

scientific measurement.

I confess I am confounded at your automatic equation of immaterialism

with spiritualism. Where does that come from? I said nothing about

spirits, religion, or an "immortal soul." Why are you bringing those

concepts into the conversation?

Are you making an error of logic like this?

Anyone can see that is not a valid argument.

You express incredulity at the very idea of an immaterial mind.

The straightforward answers are:

You ask about "a physical substrate behind experience. There is no